THE HOLY LEAVEN: APOSTOLIC CONTINUITY IN THE SYRIAC, CELTIC, AND GAULISH CHURCHES

“The kingdom of heaven is like unto leaven, which a woman took, and hid in three measures of meal, till the whole was leavened...”

Matthew 13:33

By Bp. Joseph (Ancient Church of the West)

INTRODUCTION

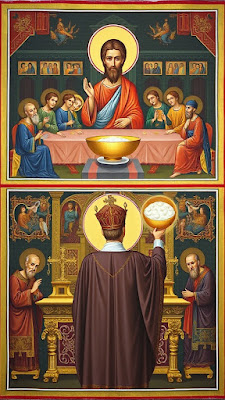

In the divine economy of salvation, God has continually chosen to work through material means to communicate His grace. From the anointing oil of the prophets to the hem of Christ’s garment that healed the bleeding woman (Mark 5:25–34), the physical world is not cast aside in the Christian faith but sanctified. Nowhere is this principle more evident than in the Holy Eucharist, wherein the Incarnation continues to be made manifest through bread and wine transformed into the Body and Blood of Christ.

Within the Assyrian Church of the East, a unique tradition has preserved an unbroken material link to the Last Supper - “Makhmarta Qaddishta” (ܡܚܡܪܬܐ ܩܕܝܫܬܐ), or the Holy Leaven, called “Malka” (ܡܲܠܟܵܐ). This consecrated yeast, said to be traced back to Christ and the Apostles, has been used in the preparation of Eucharistic bread for centuries in the Assyrian and Chaldean Churches, first referenced in the 9th century and formalized in East Syriac canon law in the 14th and 15th centuries. Yet this tradition of a living loaf was not exclusive to the Far Eastern Churches of Persia and India. Early Celtic and Gallican Christians also practiced a form of Holy Leaven, reflecting a broader apostolic and biblical principle of sacramental continuity carried out into the peripheries of the world by the Ancient Church.

BIBLICAL FOUNDATIONS OF HOLY LEAVEN

The use of leaven in Scripture carries profound theological significance. Though leaven is sometimes used negatively, symbolizing corruption (1 Corinthians 5:6–8), it is also a sign of the Kingdom of God and divine transformation. Our Lord declares, “The kingdom of heaven is like unto leaven (zymē, ζύμη), which a woman took, and hid in three measures of meal, till the whole was leavened” (Matthew 13:33). Just as a small amount of leaven permeates and transforms the whole, so does Christ’s presence in the Church through the consecrated materiality of the Holy Eucharist.

The use of leavened bread for the Eucharist is deeply rooted in the biblical tradition. The Old Testament shewbread (Lehem haPanim, לֶחֶם הַפָּנִים), kept perpetually before the Lord in the Tabernacle (Exodus 25:30), was leavened. Likewise, in the New Testament, the Greek word used for the bread of the Last Supper is “artos” (ἄρτος), which typically refers to leavened bread, versus the word “azymos” (ἄζυμος) used for unleavened bread in the New Testament (Matthew 26:17, Mark 14:1, 1 Corinthians 5:7-8).

THE ORIGINS OF THE HOLY LEAVEN IN THE ASSYRIAN CHURCH

According to Assyrian tradition, the Holy Leaven was established by Christ Himself, who consecrated the first portion of bread at the Last Supper. This bread, preserved by the Apostles, was later divided and entrusted to Saint Thomas the Apostle, Saint Addai (Thaddeus), and Saint Mari, who brought it to Mesopotamia. The leaven was then perpetuated through each generation by reserving a portion of the dough from the Eucharistic bread and mixing it into the next batch, ensuring a tangible, sacramental continuity.

This practice serves as a direct material link between every Eucharistic celebration and the first, mirroring the apostolic succession of bishops. Just as ordination ensures an unbroken line of authority from the Apostles, so too does the Holy Leaven provide an unbroken material connection to Christ’s own institution of the Eucharist.

Assyrian Malka, Consecrated Yeast Traditionally Held to Come from the Apostles and Connected to the Last Supper through the Apostle John

Ancient Syriac Communion Bread, Sealed with the Jerusalem Cross

HOLY LEAVEN IN THE CELTIC AND GAULISH CHURCHES

The Celtic and Gallican Churches, which maintained Eastern influences well into the early medieval period, practiced a similar tradition. The use of leavened Eucharistic bread was a hallmark of these traditions before the dominance of the unleavened azymes introduced under Frankish conquest and Norman persecution. The monastic communities of St. Columba, St. David, and the Irish Peregrini preserved a sacred portion of leavened dough, which was used to begin each new batch of altar bread, kept as a symbol of succession, just as it was in the Christian Far East.

St. Gildas, in his De Excidio Britanniae, laments the loss of the ancient traditions in Britain due to the encroaching Roman influence, noting that the “sacred customs of our fathers are scorned by the new masters.” This could well refer to changes in Eucharistic practice, including the move away from leavened bread.

Similarly, the Gallican Church, before Carolingian reforms, followed a Eucharistic tradition resembling that of the East, influenced by early missionary activity from the Near East and Egypt. The Council of Tours (AD 567) upheld the validity of using leavened bread in the Eucharist, indicating a conscious retention of apostolic customs.

PATRISTIC TESTIMONY AND THEOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The preservation of a sacred, consecrated leaven is deeply rooted in the Patristic understanding of sacramental grace. Saint Irenaeus of Lyons (AD 130–202) speaks of the Church’s sacraments as a continuity of Christ’s own work:

“For as the bread, which is produced from the earth, when it receives the invocation of God, is no longer common bread, but the Eucharist, consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly, so also our bodies, when they receive the Eucharist, are no longer corruptible, having the hope of the resurrection.” (Against Heresies 4.18.5)

This principle is embodied in the Holy Leaven, which ensures that the Eucharist is not merely a ritual reenactment but a living, apostolic transmission of divine grace.

St. Cyril of Jerusalem (AD 313–386) also speaks of the sanctification of material elements:

“Since Christ Himself has declared the bread to be His Body, who shall dare to doubt any longer? And since He has said it, who shall say that it is not so?” (Mystagogical Catecheses 4.1)

The Holy Leaven upholds this mystery by ensuring that every Eucharistic bread remains sacramentally linked to the bread that Christ Himself blessed.

Carbonized Roman Bread from Pompeii, Remarkably Similar to Orthodox Communion Bread

LITURGICAL PARALLELS AND SURVIVAL OF THE TRADITION

Beyond the Assyrian and Celtic-Gallican traditions, echoes of this practice exist in other liturgical customs. The early Roman Church preserved a similar tradition in the use of the Fermentum, a fragment of the bishop’s Eucharist sent to the parishes as a sign of unity. The Mozarabic Rite also retained many of the Eastern Eucharistic customs, including the holy leaven, showing that the Western Church was not monolithic in its practice.

Even today, remnants of this practice survive in monastic communities that maintain the use of leavened bread for the Eucharist. The Eastern Orthodox Churches, the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the East Syriac Churches all continue to use leavened bread, seeing it as the proper matter for the Holy Mysteries, in contrast to the unleavened hosts of the Latin Church, In so doing, they testify of the unique, living, spreading culture of the Church in the world.

THE LEAVEN OF THE KINGDOM

The Holy Leaven, as preserved in the East Syriac Tradition, as well as in the early Celtic and Gallican Churches, stands as a powerful witness to the sacramental principle of continuity. It affirms that the Church is not merely an institution of doctrinal transmission but of living, tangible, apostolic grace.

As the Lord declared, “Lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world” (Matthew 28:20). In the sacred elements of the Eucharist, especially in the Holy Leaven, the living seed of the Eucharist carried out into the world, the Church finds a concrete expression and icon of this promise - an unbroken link to Christ Himself, the true Bread of Life (John 6:35).

COLLECT

O God, who dost sanctify Thy Church through the mysteries of Thy divine grace, grant that we, receiving this Holy Eucharist, may ever abide in the unity of Thy Apostolic tradition. As Thou didst bless the bread which Thou gavest to Thy disciples, so sanctify this sacramental offering, that it may nourish our souls unto everlasting life. Preserve, we beseech Thee, the unbroken chain of Thy mercy, that the faith once delivered to the saints may remain steadfast in our midst. Through Jesus Christ, our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with Thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment