Icons in East and West

|

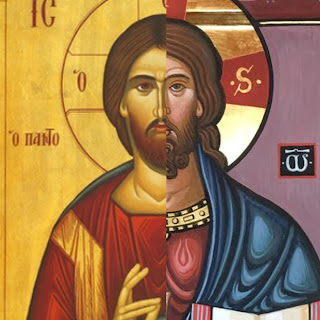

| A Romanesque Christ Enthroned and a Byzantine Xristos Pantocrator, Side by Side for Contrast |

By Bp. Joseph (Ancient Church of the West)

Introduction

In the 370’s of the Christian Era, St. Basil the Great famously expounds the equality of the Persons within the Trinity by writing: “Because we speak of a king, and of the king’s image, and not of two kings. The majesty is not cloven in two, nor the glory divided. The sovereignty and authority over us is one, and so the doxology ascribed by us is not plural but one; because the honour paid to the image passes on to the prototype. Now what in the one case the image is by reason of imitation, that in the other case the Son is by nature; and as in works of art the likeness is dependent on the form, so in the case of the divine and uncompounded nature the union consists in the communion of the Godhead.” Instead of taking away a lesson on the changeableness of metaphors, the Christian Tradition took away the concept of honor passing through an icon to its prototype, a kind of metaphysical internet, energized by the Holy Spirit, and allowing us to interact with the original, the hypostatic reality, through an image. This was brilliant, in that it helped to explain how Christians pictured iconography differently than idols - an icon stood for an absence, but pointed to a heavenly presence; whilst an idol stood for a presence, which Christians know to be absent in the heavens. This theoretical underpinning works, as long as icons represent historical personages and are not images of symbols. If they represent non-existing people, they become idols again.

The Rise of Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm has no clear Christian precedents, regardless of what Protestant scholars would later read into scattered references to the abuse of icons in the Patristic sources during the Reformation (and at this point I believe J.M. Hussey’s history differs from contemporary evidence and the teachings of the Fathers). The few references that exist are either out of context or do not appear until the iconoclasts used them in the 8th century (when there was heavy forgery and myth-making on both sides). Even Jerome’s famous translation of the iconoclastic letter of Epiphanius of Salamis (d. 403), describing his destruction of an embroidered icon hanging in a church in the early 4th century, was not only ignored by contemporaries, but directly controverted by such luminaries as St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and by classical Judaism - from whence some of the best-preserved illustrated calendars and mosaics in in Late Roman history have been found by archeologists on Synagogue floors.

Islam, with its severe reaction to Christian Roman civilization, and its insatiable desire for world domination, was the preeminent iconoclastic force in the medieval world. Islamic Iconoclasm was not just a religious force, but was also a political and social weapon, used to wipe out all remnants of the former civilizations of the conquered, uniting them into a new, pan-Arab identity. Iconoclasm was its most effective form of propaganda. Islamic military and political success challenged the way in which Christian millennialism had defined the comfortable humanist relationship between Church and State as an icon of the Kingdom of God, in which the human person could thrive in a combination of new and old, Classical pagan and Christian. As Byzantium lost the ground that Emperor Heraclius once gained in his conflict with the Persian Sassanids and against the Arabs, the new realities were hard for the Byzantine political system to bear. This feeling of dread was quickly interpreted into a theological reaction.

|

| A Romanesque and Byzantine “Hospitality of Abraham” Icon Side by Side |

The First Period of Iconoclasm

The first period of iconoclasm lasted from 726 to 787, under Leo III the Isurian (685-741), Constantine V (718-775), and Leo IV the Khazar (750-780). Leo III was a powerful general from the Syrian boarder country, raised under Jacobite influences, only coming into the Chalcedonian milieu after his ascension to the throne. In Syria he had successfully waged war against the Arab Caliphate, and established his reputation as an aggressive, effective leader. After his successful usurpation of the throne, he proclaimed his mandate to rule as a purification of the Church and proclaimed a military and religious policy that resonated with the Byzantine military faction, which was shuddering from the sudden loss of military prestige and domination that Heraclius had established a century before. Leo also provided a clear reason for the Byzantine loss of God’s support – the Christians had images, but the Jews and Muslims did not. To what extent Islamic and Jewish origins of iconoclasm are still hotly debated by scholars, but regardless of the legends that cropped up in the 9th and 10th centuries regarding Jewish soothsayers and Arab Caliphs, the success of the Caliphate at uniting the territory of Eastern Rome and the Persian Empire, along with the conversion of Khazaria to Judaism (in 682), undoubtedly shook the Ancient Christian Empire’s surety of its own mandate. It is also interesting, while inconclusive, that two of the iconoclastic emperors took wives from among the Jewish royalty of Khazaria. Heaven had seemingly turned against the Byzantines, and a radical policy must be enacted to correct the faltering nation. The proof of this policy’s correctness was established by the military success of the iconoclast emperors, which seemed to prove the efficacy of their theory. Leo’s first act of Iconoclasm was the destruction of the Icon of Christ above the entrance to the palace, thereby officially declaring the Empire’s rejection of Christ’s iconic presence within the State. The consequences of this action were to echo throughout the next one hundred years, and end in a monastic rejection of the authority of the emperor over the Church!

St. Germanus (634-740), the writer of “On the Liturgy”, attempted to resist the imperial heresy with his great “Silentia”, a stubborn resistance to state pressure on the Church to eradicate iconography, but was forced to resign after the desertion of two disloyal bishops. Germanus was replaced with Anastasius, who went on to issue patriarchal decrees against icons and removing the icons from the Hagia Sophia. Artabasdos, brother-in-law to Constantine V, briefly usurped authority and supported the reinstating of icons. He only ruled for one year, between 742-743, and was defeated by Constantine V when he returned from his campaign against the Arabs. Anastasius waffled between the two positions of violent iconoclasm and passive iconodule support, finally having his eyes put out by Constantine. His “repentance” and return to iconoclasm saw him reinstated as Patriarch, living until 754.

In 754, Constantine V convened Iconoclast Council of Hieria, without the approval or attendance of any of the patriarchs, Anastasius having just died a few months before. Constantine convened a self-proclaimed "Ecumenical Council" in the vacant see of Constantinople, attended by an assortment of bishops that had been hand-picked by the Emperor himself. The bishops invited declared the theological statement written by the Emperor, called the “Peuseis”, was true, outlawing icons, anathematizing those who kept the ancient tradition of icon veneration. However, the council also tried to forestall violence, warning against destruction of churches. This caution fell on deaf ears as the military successes of the iconoclast government became a rallying cry to all levels of society to take up the cause against idolatry, leading to the destruction of churches, desecration of relics, and the replacing of religious scenes with secular hunting and racing themes in public places.

The Reign of “St.” Irene

Empress Irene (752-803) became the regent for their son, Constantine VI (771-805) after the death of her husband, Leo the Khazar, in 780. Empress Irene called the 2nd Council of Nicaea in 787, who elected Tarasios (a known supporter of icons from a family that had been famously persecuted at court for their support of the iconodule monastics) as Patriarch in preparation, herself attending the council as the Imperial Representative. She had fallen under the influence of St. Theodore Studite, the radical monk who proposed the emancipation of slaves and the separation of Church and State for the first time in history. With his ethos as a guide, Irene successful saw the restoration of icons in the Great Church. Her religious fervor, however, seems to have ended with icons, because the rest of her reign was practically disastrous for the Church, and saw both the alienation of the Pope in Rome, and also the crowning of a rival Emperor, Charlemagne the Great, due to her desire for power, her belittling of Roman Tradition, and her deposition and blinding of the rightful emperor, her son!

Irene was a successful ruler while she functioned as regent to her son, Constantine VI, who was only 2 at the time, he rebelled against his controlling mother, idolized the person and policies of his father, and murdered his elderly consul at the age of 17. He divorced the wife his mother had arranged for him to marry, Maria of Amnia, taking a concubine, Theodota, as his consort instead. This action sent shockwaves throughout the Church in the East and well as the West, causing a “Moechian Schism” between Patriarch Tarasios and the supporters of St. Theodore Studite. After intermittent two cycles of deposition and enthronement by the military iconoclast supporters of Leo’s Isurian rule, Irene finally deposed and blinded her son, sending him to a monastery where he died of his wounds. This set off the course of events in the West by which a rival Holy Roman Empire would be established, and the cultural rifts separating the two halves of the Roman world settled into administrative and imperial competition. Regardless of the ardent support of the monks, Irene’s reign ended in ruin, and the empire quickly fall apart.

Nikephoros I (Irene’s treasurer) usurped the throne and forced Irene into abdication and a nunnery, and he and his co-emperors, his son Staurakios and his son-in-law Micheal I Rangabe, continued the policy of supporting the pro-icon faction of the Church and Court. Micheal I’s son, Niketas/Ignatios (798-877), later became the Patriarch of Constantinople under Theodora, but fell out of favor with Michael III and was replaced by Photios the Great. Unfortunately, Nikephoros was unable to sustain the military might of the empire, and a series of failed campaigns against the Arabs and the Slavs seemed to prove to the military that the veneration of Icons truly was the source of God’s wrath against the Empire.

Second Period of Iconoclasm

Second Period of Iconoclasm began in 814 and 842, started by Leo V the Armenian (775-820), a usurping general who forced Michael I to abdicate, continued by his general, Michael II the Amorian (Ruled from 820 and died in 829), who assassinated Leo V, and the Amorian’s son, Theophilus (813, becoming co-emperor with his father in 822, assuming the empire in 829, and dying in 842). Theodora (815-867), wife of Theophilus, regent to their son Michael III (840-867), restored icons in 843. Methodios (788-847) was elected patriarch and restored the icons, making the proclamation that is read at the “Sunday of Orthodoxy” from the Synodikon of the 7th Ecumenical Council -

“As the Prophets beheld,

as the Apostles taught,

as the Church received,

As the Teachers dogmatized,

as the Universe agreed,

as Grace illumined,

as the Truth revealed,

as falsehood passed away,

as Wisdom presented,

as Christ awarded, thus we declare,

thus we assert,

thus we proclaim Christ our true God

and honor His saints, in words,

in writings,

in thoughts,

in sacrifices,

in churches,

in holy icons. On the one hand, worshipping and reverencing Christ as God and Lord, and on the other hand, honoring and venerating His Saints as true servants of the same Lord. This is the Faith of the Apostles! This is the Faith of the Fathers!

This is the Faith of the Ancient Christian!

This is the Faith which has established the Universe!” (From the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America’s official service usage)

|

| Christ in East and West |

Rather than being a clearly cut issue between East and West, while agreeing in principle, the Roman Church never fully ratified or incorporated the 7th Council into their canon law. Instead, Charlemagne held his own local council in the Lateran and proclaimed the use of images and statues without giving them any form of proskynesis. This, in turn, was understood to be a “completion” or “affirmation” of the Byzantine Council and counted with the Acta of said council. Charlemagne took every opportunity to question the validity of the reign of Irene, the Council she sponsored, and the theology she endorsed, because, not only did she kill her son and true heir to the throne, but she claimed for herself the dignity that only belonged to the true Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne himself.

Summary

This is how the “glory of the king”, the category that St. Basil himself had used to explain the correct use of holy images, came to declare, modify and reinterpret the “glory of the icons”, and why we have three very different approaches to imagery within Christianity today - Iconophilic, Iconoclastic, and Iconodulic. Within the Byzantine Tradition, a clear “Iconodulism” emerged, where icons are treated as supernatural “windows into heaven”, miracles are expected from them, and icons have a special theological place within the Church, where all honors are bestowed upon them and they are treated as living saints. Within the West, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the Church of the East, another, more balanced position was held, that of the “Iconophilic” treatment of holy images and symbols. This approach treats holy images, crucifixes, statues of Christ, the Holy Virgin and the Saints and Angels as holy, with respect, and giving them a kind of honor, without treating them like they are alive or as if the saints “see through them.” They carry our honor, but they do not carry the presence of the saints, since they are united to God in the power of the Holy Spirit, and He is is everywhere present and filling all things. The last position, often illustrated by Protestants, is iconophobia, which believes any images of religious themes are innately idolatrous and sinful. This attitude is defeated by Scripture and Tradition, but it still survives in a kind of unthinking anti-Catholicism that motivates many of these communities. “If it looks Catholic, then it must be bad.” Such an attitude, while unfortunately prevalent, does not help to explain history or to avoid idolatry, since literally anyone or anything can be inappropriately exulted before God and made into an idol by the sinful human heart.

|

| The Resurrection Icon in Eastern and Western Styles |

Comments

Post a Comment