ON THE ART OF ARGUMENTATION

|

| The Great Chain of Being in De Rhetorica Christiana, AD 1579 |

INTRODUCTION

My first introduction to the rhetorical arts came as a young child in a small Baptist church, attending the multiple sermons that my father preached from the high walnut pulpit, silhouetted against stark white walls under a blank walnut cross. Three times a week, thousands of times over the course of my first 20 years of life, my dad would reason, plead, tell stories dramatically, sing and even cry from the pulpit, trying to convey the depths of his personal experience with God in our small community of dedicated brothers and sisters. Little did my father know that he was practicing an art passed down from Aristotle and the Ancient Greek Sophists, through the Medieval Roman Church, and into the bones of freeborn American Protestants. Little did I know as a child that these principles of persuasive speech would lead me into a life of learning, writing, speaking, an even more formal relationship with the Logos, and a cultural interaction with the Greek culture that had initially fostered the art of rhetoric and argumentation. In practicing this discipline, I now understand the ancient Greek and Roman definition of truth and beauty, and see how this appreciation led to the conversion of the Western world to Christianity, the establishment of the principle of synodality (senatorial conduct through the rules of rhetoric, laid out by Aristotle and perfected by Cicero) within the Ancient Church, and the reasonableness and egalitarianism that undergirds our English Patrimony. Rhetoric, in the positive sense, is the thread that weaves together the tapestry of my religious, secular and social life, and I am only now realizing it.

ORIGINS

The citizens of city-states like Athens, Sparta, and Corinth developed public speaking as an art form in ancient Greek culture. In these states, adult male citizens relied on speech-making to convince their neighbors to cooperate on political and religious issues. They established political will through shared identity, values, rituals, and vigorous communication in the public forum. They responded to this speech by voting on pottery shards, called "ostraca" (from whence we derive the term "ostracism"). This tradition developed into schools of speaking around the time of the great Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, propagated by Sophists. They often taught manipulative tricks to sway the audience to the will of the speaker. For this reason, Socrates and Plato were very skeptical of the art of rhetoric. Aristotle reexamined all these traditions in his seminal text, "On Rhetoric." He admitted that while the emotional and deceptive techniques commonly used in rhetoric were problematic, the functional utility and the ultimate goodness of discourse based upon "logos" (truth and beauty), ultimately outweighed the negatives. The Aristotelian style of rhetoric relied upon plain facts understandable to the public, allowing for accurate communication and cooperation based on mutual agreement and compromise. Aristotle taught that rhetoric was "a rather pure and theoretically sound method aimed at a cooperative search for cognitive truth (Walton 2012, 7)" and as such, he showed how logic, rhetoric, and dialectic were all connected to the art of argumentation. This approach established one of the most important aspects of modern civilization. It allows for a representative process, logical and consistent thinking, and the pursuit of objective scientific truth (Zarefsky 2005, 7-8).

|

| Cover Page from Rhetorica Christiana, an Early Work of Christian Apologetics |

|

| A Cruciform Rhetorical Pattern for Christian Doctrine |

|

| The Relationship Between Church Fathers, Early Philosophers and Roman Statesmen in the "Tree of Rhetoric" |

|

| The Ultimate Organization of All Topics in the Human World Around the Cross |

|

| Angelic Inspiration for the Orator and Preacher |

|

| Christ and the Sermon on the Mount as the Ultimate Example of Rhetorical Art |

|

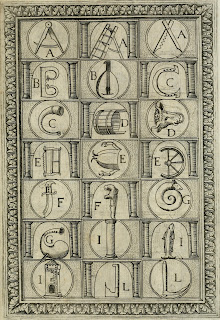

| Tools for Mnemonic Aid and the Construction of Rhetorical Mind-Palaces |

|

| The Cosmos of Philosophical and Oratorial Design |

|

| The Rhetor as an Alchemical Figure Who Unites Heaven and Earth, Nature and Man, Religion and Science, Expressing the Highest Conceptions of Human Culture |

|

| Rhetoric's End Goal is to Express Truth to the People in a Way that Allows the Divine Logos to Manifest in the Midst of Human Actions |

BASICS THEORY OF RHETORIC

Aristotle taught that truth and beauty are the most powerful basis for compelling speech, not emotion or manipulation. Every speech requires its unique rhetorical style, but all speeches share the same objective - persuading the hearer. There are only three methods of persuasion in the rhetorical tradition:

ETHOS - PRESENTING CHARACTER

Aristotle identifies "ethos" as how one perceives a speaker influences how one listens to them. Experienced, trustworthy, credible character helps the audience to see speakers in a positive light. Intelligence, strong personal character, and goodwill are the attributes that Aristotle identified as vital to someone's "ethos." These should generally be a part of the authoritative rhetor's personality already. However, familiarity with the material covered helps one present a successful image of "knowing your stuff." Expressing the appropriate emotions at the right time also helps to establish credibility. We must also adapt how we speak to each audience - passionate and polemical language works well with youth, but cautious, balanced views appeal more to the aged (Aristotle 2008, 111, 125-126, 142, Zarefsky 2005, 54).

PATHOS - APPEALING TO EMOTIONS

Aristotle sees that how an audience feels about an issue affects their judgment. Fury creates condemnation (Aristotle 2008, 87). Pity creates a more favorable verdict in a court case. Audiences are not entirely rational, so speakers must be aware of emotions and be able to understand and control the direction of an audience through the skillful use of emotion in themselves and the kinds of words used (Aristotle 2008, 111). Emotions have triggers or "causes," so evoking the needed emotion is just a matter of bringing up the right cause. Aristotle defines anger as the pain of being slighted with the pleasure of expected revenge. To whip a jury into a fury against a defendant, a lawyer must show how their identity or values have been insulted and that the defendant's response has been insufficiently penitent (Aristotle 2008, 87). Fear can be easily created by painting vivid mental pictures of imminent danger (Aristotle 2008, 100). Create pity by showing that someone suffers undeservedly (Aristotle 2008, 111). To inspire pity, one must argue that they are suffering and that this suffering is unjust, not equal to the crime or mistake, or that one is truly innocent. An audience will advocate for and take up the offense of one they feel has been unjustly treated. Discover the cause of the emotion and discover the key to an audience's reaction.

LOGOS – PRESENTING A WELL-REASONED ARGUMENT

Aristotle argues that plain facts and sound reasoning are the best ways to convince people of any given point. This is the most effective way to present an idea if the audience is somewhat reasonable. There are two ways of arguing, according to Logos. The first is implicitly by telling stories that point toward the correct answers without the speaker having to say too much (Aristotle 2008, 137, 182, 221). Alternatively, one can explicitly communicate the reason in a chain of logical inferences, which Aristotle calls "enthymemes" (Aristotle 2008, 137). These techniques form the core of Aristotelean Rhetoric, starting with accepted premises, arguing using supporting examples or facts, and concluding things that are probably true, not definitely true (Zarefsky 2005, 69, 101). It is the argument from probability since people do not argue over certainty (Zarefsky 2005, 10). Sometimes, this simple structure is enough, but other times, it is necessary to show the argument by extensive examples, either from tradition or pure logic. Professor Zarefsky points out that argumentation relies on informal rather than formal logic. One must screen the process through the audience's common sense, which derives its veracity from personal experience (Zarefsky 2005, 16). The rhetor must decide what evidence is appropriate to win over his audience, and one only develops this sensibility by practice and experience.

THE LATER DEVELOPMENT OF RHETORIC

Aristotle created the foundation of rhetoric by introducing his laws of argumentation, which showed that truth and virtue are inherently persuasive and preferable to all else. Through the use and development of these principles in the Roman Senate and the Medieval Church, Aristotle's ideas expanded into three separate arts of legal rhetoric, the informal logic of political argumentation and the formal, mathematical certainty of symbolic logic. The basis of modern argumentation is informal logic, which relies on the language and experience of the audience for validity and not upon structure alone (Zarefsky 2005, 14-16, 79). The structure of an argument is determined by what is perceived to be the most persuasive to the audience, with thesis statements called "claims" and support made from factoids or sub-arguments based on reason called "warrants." Warrants are statements reasoning for the desired end conclusion, often called "supporting statements" in the classic thesis form (Zarefsky 2005, 63-64). The "defense" is a counterpoint to the warrants, counterclaims, dismissals, or reinterpretations offered by the opposing party within the argument (Zarefsky 2005, 45-46). How the argument proceeds to explain the claim against attack defines the precise parameters of the "pros and cons" of an argument, and this point of clarity between the two views is called "stasis" (Zarefsky 2005, 38-39, 43). One judges criteria by a quality called "topoi," which are common issues of logic, knowledge, cultural values, authority, observability, and issues of ethics and attitude like fairness, openness, and kindness in a debate (Zarefsky2005, 35). One establishes these "places" by conventions that differ between disciplines, cultures, and personalities and are therefore not a matter of consensus but rather define the preconditions of an audience's expectations in an argument. The common goal of argumentation in the modern form is to agree on the essential issues genuinely and agree to compromises so that we can form new perspectives. The best course of action can then be determined to apply the new resolution (Zarefsky 2005, 7). The modern practice is more pragmatic and less absolute than the ancient rhetoric in the Aristotelian sense, which always attempted to establish a sense of the objective truth. In this, we are inferior to our fathers.

STRUCTURE, STYLE, AND DELIVERY

Stating one's case and proving it are the only essential parts of argumentation. However, an introduction and summary are valuable in helping the audience understand the material. Traditionally, rhetoric requires a four-part structure - Introduction, statement, proof, and conclusion. An introduction tells people what one is talking about, establishes authority and character, and should be used to give general context and needed definitions. Next, one narrates an interpretation of events. This storytelling appeals to emotions and is the section where one can appeal to pathos effectively. One offers proof to state the facts of a narrative and to counter any perceived counterarguments from the opponents. After this, the conclusion helps to summarize the narrative and warrant parts of the speech and is an excellent place to leave an emotional appeal. One should take care to appeal personally to the audience and to make them feel positive towards them. Finally, a short call to belief, action, or solidarity should be made, often by leaving out conjunctions and bringing attention to short, solid phrases that end the speech. Only facts truly matter, but audiences are also impressed with the beauty of a speech, which helps them to remember and respond positively to the truth presented. Performance of a speech, clarity, enunciation, elegance, simplicity, concision and correct grammar all contribute to a speaker's perceived power. Speaking in vague and unclear terms weakens an argument and makes it ugly. One must be careful of metaphors because they quickly cloud an issue and make it unwieldy. It is not just what one says that matters, but how one says it. Pause, speak naturally, tunefully, and do not attempt to be overly poetic. Overly affected or stylized speech only succeeds in alienating the audience (Aristotle 2008, 171-208, Zarefsky 2005, 48-50).

LOGICAL FLAWS AND FALLACIES

In contrast to these primary ways to create convincing arguments, there are also many ways to create fallacious arguments. The "ad hominem" ("to the man") fallacy is a classic example and is when one dismisses an argument because of the identity of the one presenting it. "He is a peasant, so he is not qualified enough to testify about what happened in court." Implied insults do not prove a theory fallacious. There is also the "genetic fallacy," when one dismisses an idea or argument because of its origins or history. Intellectual people often confuse an argument's logic with its history. The "slippery slope" fallacy thinks that A will lead to B, and B will lead to C, so one should dismiss A, which is only a wrong reason when there are no concrete processes connecting A to B and B to C. The "argument from ignorance" is also common, which states that "No one has disproven A so A is necessarily true, or, no one has proven A so A is false." Cherry-picking evidence and confirmation bias are innate difficulties built into human psychology. A clergyman will only teach the positives of his religion, a politician will only bring up the policies that worked, and a personal trainer will only take pictures of people who lost much weight to put on their wall. To avoid this, one must seek out all the facts, not just supportive data. One must seek to falsify through disproving an argument with hypotheticals. If one cannot falsify the argument, then the evidence has been stacked and is not valid. Humankind does not believe what we see: we see what we want to believe. We ignore, suppress, or overlook data that might disconfirm our ideas. Appeal to emotion and populism are techniques the disingenuous debater uses - groupthink, popularity, and historical or traditional perspective all pull on this fallacy. The appeal to tradition is also an emotional argument because traditions are tied to identity, identity to the definition of self, and the self is the most fundamental reality people accept. The "strawman argument" occurs when one intentionally or unintentionally misrepresent an argument to defeat it more easily, and then criticize the claim based on a weakened argument. To avoid this problem, evaluate the most potent argument of any claim. We must be able to argue for the opposing positions and switch places with our opponents, developing a solid imagination for argumentation. People usually do not believe something because they are stupid, and one must give others the benefit of the doubt regarding their motivation. The values behind the most valuable debates are applying the principle of charity, seeking the truth, and not trying to score a cheap shot or an easy victory. Most importantly, avoid the fallacy of relativism. Relativism occurs when one illegitimately argues that nobody is wrong and that one needs to express "their truth." Relativism is the reasoning - "X is true for me and false for you. Y is true for you and false for me." Objective truth cannot exist in a contradiction, according to the nature of reality and stated in Aristotle's "law of non-contradiction" (Aristotle 2018, IV) and to deny the existence of objective truth denies the necessity of communication and denies the possibility of cooperation on a fundamental level (Aristotle 2008, 159-178, Stearns 2015, Zarefsky 2005, 78-86).

RECENT DIFFICULTIES – REJECTION OF RHETORIC BASED ON MODERN CRITIQUE

Unfortunately, today the subject of argumentation has fallen into disuse in our contemporary culture, but it is essential to the function of law, democracy, and the liberal arts in education (Zarefsky 2005, 1). "Originally, argumentation was the heart and soul of rhetorical studies, and rhetoric was regarded as one of the seven basic liberal arts. During the intervening centuries, rhetoric was separated from its most intellectual elements, argumentation was taken over by philosophy, and formal logic (especially symbolic or mathematical logic) was regarded as the prototype for all reasoning (Zarefsky 2005, 2)." Many aspects of persuasive speaking, including the name "argumentation" itself, and the use of rhetoric, dogma, and logical imperatives are considered harmful. Many argue that rhetoric is an aspect of oppressive white male patriarchy, bound up with the sexism and genderism of Western civilization, and a tool for the oppression of women and minorities within the common academic and political references (Burris 1982, 51–74, Koertge 2013, 1). Dr. Andrea Nye, a professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin, argues that traditional argumentation is a tool for the patriarchal oppression of women, saying, "Logic in its final perfection is insane (Nye 1990, 171)." Because of this negative ideological trend within our greater society, the siloing effects of social media, and the loss of the public forum, we are more divided and polarized than ever. We cannot hear or make arguments in good faith and for the betterment of public life using the algorithms of contemporary commercial communication.

CONCLUSION

As I contemplate the breadth of rhetoric as an art form, I realize that we desperately need to return to the tradition that Professor Zarefsky describes as "fairness" and tolerance in argumentation (Zarefsky 2005, 100-103). Argumentation is essential for restoring public life and functional democracy worldwide. Northern Europeans and Americans are now deconstructing the traditional approach in a flawed attempt at "multiculturism," popular postmodernism, and a lack of appreciation for the logocentric philosophy that undergirds the Aristotelian approach to human experience. The third world of Asia and Africa are confused by the West's abandonment of principles that they have just begun to comprehended and implement in their public and religious life, lifting millions out of poverty and disease, rejecting intolerant religious wars and totalitarian governance. Various competing identities and politicized academic disciplines within the first world actively discard principles of argumentation, and proponents of Islamization, Slavophilia, and Sinocentrism undermine its uses internationally. Marxist ideas of power and revolution, which reject the Aristotelian understanding of truth and beauty as the primary convincers of the human soul, are popular again amongst Western elites. The contemporary Marxist dialectic, transferring economic arguments of class and status to sex, gender and intersectionality, obliterates the perceived need for dialogue, discourse, compromise, and pragmatic statecraft in countries that have only known peace and wealth over the last century. The Aristotelian tradition of critical thinking and rhetoric is the only presuppositions upon which modern science, medicine, and an open, democratic society operate - but if it falls, there is nothing to replace it. The Western legacy of equality, human rights, individuality, innovation, and peace can only continue if the values of benign argumentation experience a true renaissance and resume their central role in academics, politics, culture, and religion. Then, we can return to the view of human value that reflects the Imago Dei, and our relationships can truly express the truth and beauty of the indwelling Logos.

|

| The Highest Expression of the Logos is to Present the Incarnation, Perfect Life, Sacrificial Death, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus Christ, the Word of God |

Aristotle. 2018. Metaphysics. Translated by W. D. Ross. Boston, Massachusetts: MIT University Press.

Burris, Val. 1982. The Dialectic of Women’s Oppression: Notes on the Relation Between Capitalism and Patriarchy. Berkeley Journal of Sociology 27 (1982). Berkeley, CA: University of California Berkeley.

deLaplante, Kevin. 2009. “The ‘Straw Man’ Fallacy.” YouTube video. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5vzCmURh7o

Koertge, Noretta. 2013. The Feminist Critique [Repudiation] of Logic. PhilArchive blog. Accessed July 19, 2022.https://philarchive.org/archive/KOETFCv1

Nye, Andrea. 1990. Words of Power: A Feminist Reading of the History of Logic. Routledge Publication: Oxfordshire, UK.

Stearns, Paul. 2015. “22 Common Fallacies.” YouTube video. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUO2asxV-J0

Wilson, Douglas. 2007. Media Argumentation: Dialectic, Persuasion and Rhetoric. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Zarefsky, David. 2005. Argumentation: The Study of Effective Reasoning, 2nd Edition. Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses Company.

Comments

Post a Comment