|

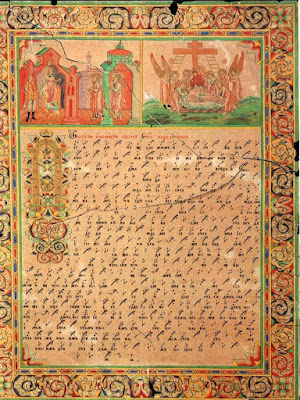

An Ancient Icon of St. Gregory the Great,

Taking Dictation of Gregorian Chant from the Holy Spirit in the Form of a Dove |

One of the most distinctive things about Eastern Orthodoxy to the Western mind, aside from the emphasis on iconography and liturgy that often seems Baroque and aesthetically overdone, is the prevalence of chanting in the Eastern Churches. While it is very different from Western Christianity today, with its emphasis on spoken prayers and repetitive, easily performed choruses, Eastern Church music actually has a much more biblical root, and also shares a common history with Gregorian chant that is mostly overlooked. The Early Church sang Psalms to melodies directly inherited from temple worship, still easily read in the Hebrew cantillation marks of the Old Testament and Psalms, which are still a part of the Hebrew writing system today.

|

| Curved Dots, Dashes and Hashmarks Represent Chanted Tones in Biblical Hebrew |

|

| Cantillation Marks Reduced to Modern Musical Notation |

St. Ephrem the Assyrian and St. Romanos of Antioch wrote hymns within this Semitic musical tradition, sung to "modes" (variants of inherited melodies) that were found in the Psalms themselves. A quick comparison between the realizations of melodies by chanting experts, such as the musical reconstructions of Susan Haik-Ventura, shows a close similarity between the contemporary Jewish chant and the chanting from the East Syriac Tradition.

|

| St. Kassiani, Byzantine Poetess and Composer |

It is historically significant that all of the ancient hymnographers were from the Aramaic/Hebrew Tradition, not the Greek-Speaking Philosophical Tradition. The singing style that is commonly called “Melismatic” in Latin and “Kaliphonic” in Greek is derived from the Antiochian school of singing. The Hebraic roots of the music is obvious in the liberal use of 8-note minor scales, melisma flourishes and microtonality, unison, congregational singing (both ecclesiastical antiphonal choirs and general responses in the congregation) and modalities that are not found in Classical Greek music (5-7 note modes not named with place names as in the days of the Great Philosophers).

The following illustrations show the Ancient Greek notation for contrast -

|

| The Seikilos Epitaph, One of the Earliest Complete Greek Musical Inscriptions, Dating to Approx. AD 100 |

All of these modes center on four-note scales, called “Tetrachords”, which were limited by the strings of the Greek Lyre, and made songs essentially narrow range chants in the ancient world.

|

| A Greek Krater Illustrating a Greek Musician Playing a Lyre and Pouring Out a Drink Offering before an Onlooking Raven |

Chanters of the day noted that these hymns were sung in the "Syrian Style" (see the early 4th century pilgrimage to Jerusalem and surrounding area by Egaria), and that these were the models on which the Greek-speaking Christian world based their Church Music. Thus, the Syriac Christian preservation of ancient Hebrew Psalms gradually replaced the tetrachordal music of Ancient Greece and created a new form of modal music which was recorded and passed down in the East with the invention of musical notation in the 6th century, and preserved in skeletal outline in Gregorian chant roughly a century later.

|

The Byzantine Wheel of Modal Notation

|

|

| A Contemporary Illustrated Chant Page, Using Byzantine Style Neumic Figures |

|

| Calligraphic Byzantine Neumes |

|

| The Development of Byzantine Neume Notation into Western Gregorian Notation |

With the advent of notation in the 6th century, these melodies were written down and preserved, and formed the basis of the most consistent and ancient musical tradition in continual use in the contemporary world, which much ornamentation and evolution. Later, unadorned versions of these melodies were recorded in the West, and formed a substantial influence in the work of St. Gregory the Great (or "Dialogist" as he is called in the East). Minus the ad libbed flourishes and "riffs" of the more ornate Syrian styles of singing, these melodies became the smooth, monotonal, unison style of singing that we now associate with Medieval Western Church Music.

|

| The Theory of the Guidonian Hand, Enabling Symbols for Three Octaves to be Silently Signed to a Choir by the Head Chanter. Diagram held by the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, Oxfordshire, UK. |

|

| An Anonymous Illustration from the 8th Century, Explaining How Choir Masters would Sign Notation for Singers to Sing, Eliminating the Need for Sheet Music or Sight Reading in the Modern Sense. This Practice Led to the Development of Writing Music on Four or Five Lines, which is Characteristic of Western Musical Notation Today |

|

A Selection of Traditional Gregorian Notation on a Staff, Which Represents the Five Fingers of a Capellmeister, Who Would Show the Tone by Pointing to a Finger

|

Eastern Orthodox Church Music substantially "Westernized" after Peter the Great took over the Russian Church in AD 1667, reforming chant along Roman and Reformed lines, resulting in the Slavic Tradition of Orthodox Music that is not only highly aesthetically appealing to Western ears, but also clearly strives to maintain some modal continuity with its ancient predecessors. Thus, Russian music uniquely represents a reunification of Church music in a truly remarkable way, showing the growth and development of the musical tradition in both the East and the West. Thus, Eastern Orthodox music becomes fully "Western" to our ears, and simultaneously points us back to our own musical tradition's roots in the Old Testament and Psalms, and connects us to the worship of the 1st century Church!

Comments

Post a Comment