On the Difference Between Honor and Worship from a Western Orthodox Perspective

"Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God am a jealous God..."

- Exodus 20:4-5

By Bp. Joseph Boyd (Ancient Church of the West)

The Church refused to honor Caesar through ritual sacrifice, such as burning a pinch of incense or sacrificing birds or small animals, as was the process to recognize the Emperor as a god. They did, however, honor their rulers with prayers for health, long-life and salvation.

|

| Senators Burning Incense to the Emperor |

|

| Emperor Trajan Burning Incense to Diana |

|

| A Merchant Publicly Burning Incense to the Emperor in a Funerary Decoration |

|

| A Roman Coffin Depicting the Offering of Incense to the Emperor |

Later, when the Emperor revoked his claims to deity, the Christians had no problem with honoring his image (as Christ had the image of Caesar on the coin in his parable), praying for him publicly in the Liturgy (as had been instructed by St. Paul), and kneeling or bowing as was required by cultural protocols of honor.

Therefore, Christians understood that honor with sacrifice was “Adoration”, called “Latria” and due to God alone, but “honor” by outward acts of obedience and respect was not the same as the glorification of God in our hearts and the kind of wonder, awe, contrition and sacrifice of self (not merely a social putting down of one’s self, but an offering up of one's self) that occurred in the worship of God. The Father who introduced this distinction in both East and West is the extremely influential Western Saint, St. Augustine of Hippo. He wrote a discourse on Latria and the respect given to angels in the Bible, showing that there was a difference, and introduced the distinction between the words Latria and Dulia, which had the same meaning in contemporary Greek usage.

St. Augustine says, in the Tenth Book of the "City of God", Chapter 6: "But, putting aside for the present the other religious services with which God is worshipped, certainly no man would dare to say that sacrifice is due to any but God. Many parts, indeed, of divine worship are unduly used in showing honor to men, whether through an excessive humility or pernicious flattery; yet, while this is done, those persons who are thus worshipped and venerated, or even adored, are reckoned no more than human; and who ever thought of sacrificing save to one whom he knew, supposed, or feigned to be a god? And how ancient a part of God's worship sacrifice is, those two brothers, Cain and Abel, sufficiently show, of whom God rejected the elder's sacrifice, and looked favorably on the younger's."

Later, these definitions would be fully worked out in the Early Christian philosophical and liturgical system. It started with the Council of Ephesus in AD 431, when the Church was debating the term “Theotokos”, when the Fathers demanded that Christians render “Hyper-Dulia” to the Most Holy Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary. What is this? Well, it is a special kind of devotion that means “Super Servitude.” This was seen as the appropriate way to distinguish between the respect given to Saints and the reverence paid to Mary as the Mother of the Savior.

Dulia is referenced in much of the Early Church as the sense that someone gets when they are in a lower social situation and must give unearned honor to their “superiors.” It is almost always a negative word in Greek, and it implies a lower social status. The New Testament uses the word 7 times, and all the references are negative. This is why it is often translated as “slavish” or “servantly” duties, unlike Latria, which is often used positively in the Septuagint in reference to the service of God. In the Church, we respect the Saints, knowing that their holiness is from God, and we esteem them as higher in the hierarchy of heaven than we are, and so, based on the patronal conventions of Ancient Rome, we show them respect by “Proskynesis.”

Proskynesis literally means “to kiss up”, and the meaning back then was the same as the meaning now. One was expected to lower themselves in the presence of those higher in the hierarchy, bowing to those he did not know, or who were extremely high in social ranking, like dukes, princes, kings and emperors. For those he did know, with whom he had intimate interactions, kissing, bowing the head, touching the feet of the Pater Familias, or a quick bob/curtsy, was a common occurrence. It showed that one was dependent upon the person being venerated, that there was a special relationship, and that the one showing respect did not assume equality. Amongst true equals, kissing the face and holding one another’s forearms, the precursor of a handshake, was thought of as marks of respect and brotherliness.

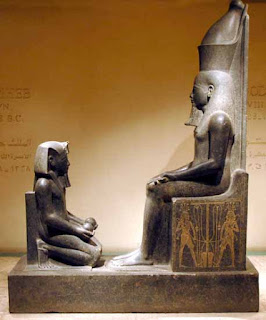

The practice of bowing to social superiors is an ancient one. We know that ancient Egypt saw worship as a sacrificial bow, when a devotee would lower himself in the presence of a god or goddess and offer up food or wine. Bowing on one knee before Pharoah was standard protocol in the Egyptian court by his familiars who were allowed to see him. Bowing outside of the court on both knees was expected of slaves, surfs and commoners. Bowing on both knees was protocol for worshippers in temples, who were granted an audience with a seated idol of a deity, and even the Pharaohs bowed on both knees in their powerful presence. Kneeling was so important, and the idea that the gods inhabited their own statues so second nature, that many Pharaohs made statues of themselves worshipping and sacrificing, to place before their gods in order to permanently represent themselves and obtain favor from their deities.

|

| A Statue of Pharaoh Offering Sacrifice to Osiris |

|

| A Statue of a Slave Permanently Offering Sacrifices to Anubis |

During the time of Alexander the Great, Greek culture came into intimate contact with Persia, and it was here that the practice of Proskynesis was learned and brought over in a Western cultural context. Before this, any man of low social rank was forbidden from approaching a freeborn Greek man without being called, and, therefore, distance was a sign of respect and submission. All freeborn citizens of the Polis were equal, so those Greeks always greeted one another with a kiss and did not bow to one another. This practice was seen as both contrived and servile, and completely unbecoming of Greek manliness and egalitarianism. Alexander introduced bowing into his court, believing that he would be worshiped as a god after death, but this was resisted by his soldiers and comrades, who thought that it was ridiculous, and the pushback against it was so strong amongst the Macedonians that even Alexander could not force the Greeks to adopt this form of "obeisance." However, after his death, it is known that his four generals retained the practice and forced the Greeks under them to honor them with bowing. This practice was retained by the later Romans, who saw it as essential to their society, so that hierarchy and dependency could be easily seen and help to maintain order within the Greco-Roman society.

|

| A Nobleman Bowing to the Persian King, Showing High Social Status |

|

| The Degrees of Bowing within the Assyrian, Persian, and Later Greek Courts |

|

| A Modern Depiction of the Court of Diocletian, Keeping the Ancient Protocols for Proskynesis of the Emperor |

In the Histories of Arian, Callisthenes, a Macedonian general under Alexander, states the Greek objections to Persian-style Proskynesis: "I declare that there is no honor fitting to man that Alexander does not deserve. But a distinction has been drawn by men between honors fit for mortals and honors fit for gods, for example in the matter of building temples and setting up cult statues and setting apart sacred enclosures for gods, and making sacrifices and libations to them, and offering hymns to the gods but eulogies to men. Most important is the distinction observed in the matter of obeisance. You greet men with a kiss, but since a god is placed higher up and it is sacrilege to touch him, you honor him in this way with obeisance. Dances, too, are held in honor of the gods, and paeans are sung to praise them. No wonder, when one considers that different honors are appropriate to different gods, while heroes receive yet others distinct from divine honors. It is unreasonable, therefore, to obliterate all these distinctions by inflating human beings to excessive proportions through extravagant honors, while inappropriately diminishing gods, as far as is possible, by offering them the same honors as men. Alexander himself would not tolerate for a moment a private individual laying claim to royal honors on the strength of some unjust show of hands or vote. How much more justified would be the displeasure of the gods against men who assume divine honors or allow others to do it for them. Alexander has more than justified the claim that he is and is seen to be the bravest of the brave, the most kingly of kings and the greatest of all generals." (Arian, The History Anabasis, 4.10.5-12.5, translated by M.M. Austin)

|

Jehu, Son of Omri, as King of Israel bows before to the Assyrian King, Shalmaneser III |

Jews had difficulty with social respect being shown in the form of full-body bowing or kneeling as well. The story of Esther shows how this practically played out. As a substitute, during both the Persian and Greco-Roman occupations, the Jews would half bow and put their right hand to the ground, which is still a position of prostration that one may see in the Eastern Churches from bowing laity or clergy towards Archbishops, Metropolitans and Patriarchs. Jewish prostrations were done in the temple, in sackcloth and ashes, during times of repentance and mourning, but this was never directed towards other people. Jews preferred to show honor by distance, embraces, kissing, and touching the head. If someone was allowed to touch someone else’s head, it was assumed that he was of higher social status or an elder with an intimate relationship to the one being touched. This is how blessings are given, and we can see this tradition continued as well within the Church. Even in modern day India, the practice of children or grandchildren touching parents’ or grandparents’ feet, and having a soft touch on the head is considered a form of blessing. This can be seen in Islam as well, where Imams will touch the heads of young men while invoking Allah’s protection.

As the Church embraced the imperial model of governance, and the role of bishops became indistinguishable from that of senators and proconsuls, much of the pre-existing protocols were used with them and their representatives, which were brought to the West by Alexander the Great and his Tetrarchs. Therefore, honorific names, titles, pectoral medallions, special colors, fancy hats, rings, and many other symbols began to be used as they had in the secular environment, but with a strong emphasis on Christian iconography. Mayors and governors in Romance countries, which kept the ancient Roman practices, also give their officials heavy gold chains and medallions as symbols of their legal authority. Many Lords and Ladies wore signet rings, just as Bishops do, and the social hierarchy effect was extremely similar. In the West, several mendicant orders arose to force reforms, such as the Clunyites, Franciscans and Dominicans; but in the East, none of these austere movements were able to wrest power out of the hands of the Emperors, who effectively kept the Church from divesting itself of these outward symbols of power by replacing overly reform-minded Patriarchs at will. This is what the West called “Caesaropapism” and is one of the enduring problems of Byzantine polity.

|

| Torah Niche from the Synagogue of Dura Europos, Painted with Icons from the Hebrew Bible, Between AD 260-80's |

|

| A Christian Baptismal Pool from Dura Europos, Showing the Virgins with Lighted Lamps, Waiting on the Bridegroom to Return |

Symbolic representations of power were not foreign to God's Covenant with His Chosen People. The ancient Temple, a plan given by God and commanded for the spiritual health of the Hebrews, was profusely covered with icons, statues of Cherubim, bulls, palm trees and pomegranates. Later, very few unadorned Synagogues are found. The earliest church buildings discovered have icons, as do the underground catacombs used by Christians in Rome for several centuries. The surviving 3rd century church and synagogue of Dura Europos shows how both covered their walls in illustrations of Scriptural stories, so as to catechize those attending worship in these buildings. Images were a part of life and useful as a technology. They were not automatically excluded by Jews or Christians as being excluded by the Ten Commandments, although later generations would react to abuses of these depictions and take decidedly less balanced approaches.

|

| An English Icon Defaced by Iconoclastic Reformers in the Late 1500's, Kept in Its Defaced State as a Testimony to the Destruction Wrought by Anti-Catholic Political Forces in the Reformation. |

|

| Protestant Moravians Practicing Divine Proskynesis without Icons, Depicted Iconographically with the Mystical Presence of the "Lamb Who Is Slain" in Heaven |

It was within this context that the East developed its theory of the veneration of icons, as first developed by St. Basil the Great and then refined by St. John of Damascus, who was later extrapolated into a complete theological system by St. Theodore of Studios. In this theory, kissing, bowing, and prostrating was not thought of as innately worshipful, but were cultural symbols of respect, loyalty and familiarity. These actions were performed in Byzantine society all the time to people who were neither godly nor particularly powerful, and so, they felt no pain of conscience when performing this actions before the Scriptures, Crosses, Icons, Churches, Relics, or Clergymen. As St. Basil the Great had described in his work, “On the Holy Spirit”, the theologians saw honor passing over the material things to God, and were confident that these symbols represented Him in a way that was not confused with idolatry. Idolatry, in their minds, was offering up praise, contrition, awe and sacrifice to false gods. Veneration was offering up honor and loyalty to symbols of God and His Saints, all of whom were real, and with whom we had a relationship through the power of the Holy Spirit. The West was never so confident, seeing how devotion to images of Saints amongst the peasantry could often blur this very fine boarder between Dulia and Latria, and so the West never officially sanctioned the kissing of icons or prostrations before them. Prostration before the Cross was seen as a penitential act, or an offering of self to God, and so we only see this performed liturgically in ordinations or public penances. They would bow towards the Cross whenever they saw it, as a symbol for Christ Himself, and kiss the Bible, as the Jews before them had done in the Synagogue. Strangely, though, the West was more liberal with the veneration of living prelates, especially the Pope, and so actions like kissing the rings of bishops were standard within the culture, to show honor towards the authority they held. The kissing of the shoes of Cardinals and Popes was actually a Byzantine practice that lasted for several hundred years in the West, but it is still practiced by the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchs today.

Western Orthodoxy agrees with the doctrinal assertions of the Eastern Churches in regards to iconography, seeing the making of icons to be linked to Christ's Incarnation and taking on visible, palpable, artistically describable human flesh; but counterbalances these teachings with those of our local councils that occurred at the time, often claiming the same name (such as the "6th Council"). As Eastern Orthodoxy has pulled into itself and redefined the Councils according to a later definition of history, anachronistically labeling Councils by number, Western Orthodoxy has a harder time, because we were still an undivided Church and held Councils in the Lateran that Constantinople sent representatives to attend, but now forgets. Our Western 6th Council commended the use of icons, but explicitly rejected their veneration as a necessity, saying that "spirits do not live in images or use them to communicate with us, as pagans believe." Thus, the West took a different course, embracing images and statuary but not venerating by kissing or performing proskynesis towards them, agreeing in principle but not in practice with the Eastern theology of icons.

|

| A Contemporary Eastern Orthodox Depiction of the Various Degrees of Veneration |

When the Reformation came around, the various theological and cultural distinctions that the Church had made were retained in the earliest substratum - so much so that Anglicans were receiving Holy Communion on double bent knees throughout the reigns of Presbyterian monarchs, who they would only honor upon a single knee. Lutherans, too, kept the veneration of Cross and Bible, and maintained the goodness of holy images for teaching the illiterate and for decorating places of worship. Quickly, however, iconoclasts took over the Protestant movement, and from Germany to Scotland, many an Icon-covered church was sacked and ancient murals were plastered over or chipped away. One of the greatest tragedies of our Patrimony was the “Stripping of the Altars”, started under Henry VIII, for the purpose of impounding the treasures of the monasteries for the government’s coffers, and extended on through Oliver Cromwell’s reign of terror, which assured that all but the most remote parishes would conform to the Puritan sensibilities of image-hating and saint-loathing Reformers. After this cultural struggle died down, Protestants forgot the unique cultural matrix where the theology of icons initially arose, and never replaced it with a systematic set of beliefs and practices. Therefore, many Protestant Bibles have beautiful illustrations, and Children’s catechetical material is profusely illustrated, but the problems of idolatry or how God sanctifies the imagination of the beholder through filling internal images with the power of the Holy Spirit is never considered. While many Protestants fill their houses with religious imagery, it is considered idolatrous for them to move that same iconography into the church building, where walls must be plain and no symbols are allowed (accept a bare Cross). However, with the introduction of slides and PowerPoint for both lyrics and sermons, often profusely illustrated, a new gray area where God is expected to use images to bless and sanctify people has emerged again in a Western Christian context. Only the Ancient and Apostolic Churches still have a good theology of how these images are to be seen and used. Contemporary Christianity is confused by art and music to the point of absurdity and threaten, once again, to bring pagan practices into places dedicated to the Name of the One True God.

Contemporary Orthodox practice has become a mixture of theology and culture, where the prohibition against sacrifice to anyone but God seems to be largely forgotten, and where bowing, kissing, prostrations, etc, all seem to mean the same thing, generally being thought as a way to give honor. This is why the method of honoring Clergy, Icons, Crosses, Bibles and Relics have all basically been distilled to bowing, kissing, and crossing one’s self (accept that one does not cross one’s self to a priest or bishop, instead, one asks for a blessing and is crossed by them). Many people practice fasting for Saints, which, as a form of sacrifice, should actually not be allowed to occur, as well as bargaining and haggling with Saints for favors, which is, again, theologically akin to magic and not the righteous sacrifices commanded by God for His people. A concerted effort needs to occur within Orthodoxy to explain and clarify these practices, so that misdirected worship and excess does not threaten the doctrinal Orthodoxy of the laity. If we can contribute anything to the conversation it would be to bring St. Augustine’s understanding of Latria back to the fore, and qualify a theory of icons with the depth of understanding that the West uniquely brings to the discussion of how to appropriately show honor to godly symbols and people, while reserving the act of giving self as a living sacrifice to God alone. This perpetual sacrifice is the duty of the baptized faithful of the Church, a kingdom of priests, who lift holy hands to the Lord and offer themselves up to God in a spirit of complete surrender, love, awe and praise, and thus fulfill the original destiny of all created beings. Such theological clarity will help us to avoid the abuses and superstitions that form with a lack of proper teaching and instruction, and avoid the overly-deferential, infantile and servile customs that elevate the clergy above their appropriate position of servants and shepherds in Christ’s flock!

|

| Christ Blessing the Byzantine Emperors in the Ancient Jewish Manner, with a Light Touch to the Head, in a 9th Century Byzantine Ivory Icon |

Comments

Post a Comment