Sola Scriptura and Intertextuality

|

| Antiphonal Response and Recitation in the Medieval Western Church, Scripture Lived Out within the Christian Community through Liturgical Forms |

By Bishop Joseph Boyd (Ancient Church of the West)

"All scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness” - 2 Timothy 3:16

“Sola Scriptura” understood as meaning the whole of the Scripture received by the Ancient Church (without artificially reducing the canon of the Old Testament by scholastic principles) and through the hermeneutical context of the Early Fathers, can be understood and received as a true principle - but not as a Protestant concept that, while proclaiming Scriptural inerrancy and infallibility, cuts out 11 books so that the Christian Old Testament matches the 8th century AD Massoretic Jewish text. The Protestant axiom, “Interpret Scripture with Scripture”, is nowhere found in Scripture. Scripture, indeed, contains all things necessary for salvation. But, only when it is understood in its Apostolic Christian context, through the writings of the Fathers and within the creedal Orthodoxy of the Church.

This has been identified in postmodern critical studies as “intertextuality”, meaning that we bring into the text the meaning of the words, and those meanings are inherited from our culture. Therefore, without a continuous and preserved biblical culture (such as we have in the Church) we cannot rightly understand the meaning of Scripture. Instead, when we believe that our own culture is sufficient for understanding, we impose foreign categories and meanings on to the text, and that creates innovation and heresy.

|

| A Getty Image Graphic Showing Intertexuality through Internal References and Quotations within the Scriptures in a Positive Light, Showing Continuity in Narrative and Cause/Effect Sequence |

Unlike the Scriptures, we observe that scholars are right in their observations of historical hagiography, and that many compilations of the lives of saints tended to be politically oriented and geared toward the credulity of illiterate peoples, rather than, as the Anglocatholic tradition has stressed, making people more literate and able to understand history. One of the interesting trends in history is the rise of the Lives of Saints as a substitution for Scripture, and the curious interplay that this often has with the loss of information and theological knowledge. The theology of late antiquity in the East and West was extremely based, philosophically and historically, upon a communal reading of Scripture. The Apostolic and Ante-Nicene Fathers definitely believed in miracles and report amazing things, but their “entertainment value” is low, and they constantly quote Scripture to lend authority to their arguments. As time goes on, some of the continuity with Scripture and early theological categories becomes tenuous, but the entertainment value increases. It is not wrong to critique this drift, or to repent and return to the integrity of the Early Fathers, but overthrowing the Church and its ancient teachings because of this drift, as many of the Reformers did, is also untenable.

All the various Apostolic churches are going through this process of reassessment, as scholarship reveals how the Lives of Saints evolved over time, showing them to be less than credible in some ways. Orthodoxy, especially, has become much more historically minded and transparent, which, instead of harming their faithful or lessening their commitment to the miraculous works of God, make the system more cohesive and clear, as well as more believable to intelligent, literate people. Another thing that we see in the Eastern Christian tradition of interpretation, the Anagogical and Mythical Interpretation Schema, makes it possible to see and remember truth in ahistorical stories, and this process has often been forgotten in the more literalist and legalistic Western context. It could be argued that many of these Vita were constructed, not as histories, but as morality plays and analogies. This is why it is so important to understand the cultural context, and not to impose our own categories on the texts.

This is the perfect illustration of the problem of intertextuality and projected cultural meaning that we are discussing -

In the East Syriac tradition there is a good illustration of the meaning drift that we are discussing. In written texts there is a bar between lines of a poem, showing where a breath was to be taken. This bar is pronounced “Hengya”. As time went on, the chanters began to chant the word “Hengya” whenever they came to this bar, instead of taking a breath, and so now, it forms the most common “chorus” in the singing of the Psalms and is a nonsense syllable. This same drift occurred in Byzantine chant, the “Terrarim” that is sung to extend chants when words have run out, and these nonsense syllables take on a spiritual meaning that are projected from the depths of combined spiritual expectation, given a mystical and symbolic nature that completely obscures their utility. Words change meaning, and sometimes meaning is lost, and sometimes meanings have to be rediscovered and repaired. It is a constant process of return and repentance, personally and culturally. This process or reassessment and recalibration is different from “Reformation”, which was envisioned as a process of iconoclasm and rejection, rather than of return and repentance, keeping the lessons learned and the experience brought from the loss and recovery of meaning. Just as we are obligated to confess and forsake our sins, not forgetting the lessons that we have learned in the process, so we are to work through these issues of meaning, authority and political misappropriation with repentance, learning from misunderstandings and abuses, insuring that such things do not happen again. The point is to preserve and curate, not to dethrone and throw out.

The Eastern Theory of Infallibility

Origen won many over to his Hellenized, gnostic, Dante-esque world of preexistent souls, little "l" logoses and big "L" Logos, incarnation, reincarnation, purification and enosis. St. Maximos liked the culture and the goal of "Telos" in "Apocatastasis", but did not like the unbiblical nature of pre-existent souls of perfection falling. Order should not fall into chaos, and perfect Angels and Human Souls should not fall from God, once they experience "union" with Him. His reasoning was good, to fall from God and Grace would imply that God and Grace were somehow insufficient. He didn't question his philosophical understanding of "union", which is where he probably should have started, so, instead, he turned Origen's system upside down and created a new one. Origen believed that Perfection was followed by Fall, and Fall was overcome through Askesis-Purification. After Purification was completed, there was Illumination, and this led back to Enosis, a restoration of the original state, but this time with knowledge replacing ignorance. Maximos starts with the opposite approach, man being created with a capacity for perfection, but with the necessity of learning and growing. Therefore, man's fall wasn't a reflection on God's insufficiency, but, rather, a reflection on man's own immaturity and ignorance. Man's nature, being imperfect, was scared by sin in its alienation from God, but, not starting out perfect, he really had not fallen very far - meaning that his basic functions were intact, his Imago Dei was still both visible and functional, and that he could, through repentance, return to the state of growth that was necessary for Adam and Eve to fulfill their created potential. In Maximos, the human conscience, without any special work, could understand the need for God, and through the process of purification, receive the gradual filling of the Holy Spirit to the place that God and Man were truly unified. The Fall had not expunged the common grace present in God’s creation and sustaining of life. While this view also helps explain some points of classical humanism and the existence of goodness outside of the Church, Maximos fails to address the great evil that exists in the world and diverges greatly from Augustine, who dealt with human and political realities with much more brutal realism - hence, the Greek world's unshakable belief in the "infallibility of perfection", while the West was largely unimpressed with essential categories of ontological infallibility, and chose to focus of functional authority and a systematic approach to administration, which came to be seen as an infallibility of office.

As "the Perfect One", Christ was thought as the prototype for this kind of perfect relation, in which there is no room for fall, or for the growth or ignorance declared in Scripture. Christ must have feigned ignorance, a kind of "holy lie", which hid his innate and unchangeable perfection. In the same way, the Greeks saw Christ, God incarnate in humanity as the Word manifest in the Greek language, therefore giving the Greek culture a precedence far excelling any other "words". There was no perfecting what was already perfected and demonstrated by God's choice. Therefore, God, in the fullness of time, chose to be incarnate for the Greeks, and abandoned the dead vices of the Jews (even though they heaped up more laws to themselves than did Moses and his law).

These attitudes are also seen in the way that the Greek Church believes that it is literally impossible for Hellenic Orthodoxy to fall into heresy, it being the correct, God-loved and supernaturally preserved Greek Tradition, making any repentance or recognition of error an impossible option in an absolutely infallible Church, while Rome both recognizes its own frailty and also recognizes the validity of those with whom it disagrees. The anthropological and ecclesial significance of the difference between Maximos and Augustine are profound, especially when considering how the Gnosticism of Origen permeated and continually informed the Greek Church, even though he was disavowed and anathamatized, flowing from Maximos' unquestionably "orthodox" reworking of his system and the acceptance of the Monophysite pseudonymous "Dionysian Corpus". The Greek reasoning is clear, "since the Greek Church's foundations could not be compromised, it being the center of the Roman Empire, seat of the Emperor and the "preserver" of inspired Greek Testaments, any divergence with the Greeks in theory or practice must be heresy, while any change that occurred with the Greek Tradition must have been valid, needed and the standard for the world." Thus, "Perfection" becomes a "Locus", and the "Locus" becomes "Authority", which, being "Perfect" cannot fail. Thus, the rather soft stance on schisms within Orthodoxy - Old Calendrists, Monastic Radicals and Fundamentalists, and Athonites - while a harsh, damning attitude on those outside the Tradition. What is interesting is, that with this attitude, Orthodox must consider the schism to begin with the use of Latin and the transferral of authority to German imperialism, as it is often so subtly insinuated that, while "technically in communion", the "Latin Church had already fallen into heresy and unorthodox praxis by the earliest centuries.” The definition of Orthodoxy, then, is a culture, and ironically, the Gentile world that the Apostles wished to exclude as unclean and in need of circumcision, not just baptism, is the exclusive new Israel.

As the Apostle Paul said in I Corinthians 10:12 “Wherefore let him that thinketh he standeth take heed lest he fall.”

The Pendulum Swings

From our reading, we have seen that there is a constant tug-of-war between two extreme impulses within the ecclesiastical and administrative context. The first is to obsessively cling to externalities as surety of correctness, and imagine that involvement with institutions is the essence of an authentic experience with God. This tendency creates increasingly complicated and hierarchical structures, focuses on centralization and consolidation of political power, and aggressively represses those who are seen as a threat to the continued expansion and regulation of the system. This can all be done with the best intentions, and it is an “incarnational principle” in a way, because this tendency builds up strong centers of spiritual authority and creates cultural stability. It is not a wrong impulse, if it can remember its own history and not rewrite the narrative so as to anachronistically obscure its own origins or what came before. If it can resist this internal hardening and self-sufficiency, it can be a beneficial force. However, as we have seen with Rome, and now, hilariously enough, with Canterbury’s insistence on its own canonical importance within the Anglican Communion, it is a hard trend to defy.

The second tendency is to decentralize, democratize, “egalitarianize” the process of spiritual experience, and to critique and deconstruct the institution through an appeal to personal authority and to God’s universality. This trend can be seen in the East through the legacy of the lay monks and elders in Russia, who lived on the fringes of society and who did not conform to Peter the Great’s centralization, or the “Old Believers” who resisted Patriarch Nikhon’s liturgical reforms and centralization. It can also be seen in the legacy of “Non-Possessors”, who believed that the Church and State had no right to coerce the conscience of the people and could not force conversion or compliance to Church Canon Law. Their point was that the Church could persuade through brotherly admonition, but could not force anything on anyone. We can see this tendency in St. Benedict and St. Francis of Assisi in the West, the Blessed John Wesley within the Anglican Patrimony, and of very many other saintly fathers who started movements of personal piety and simplicity. I see many of these trends, initially, in the Jesuit Movement, although intellectual centralization became such a powerful and heady narcotic that it became impossible to resist, leading to their attempted takeover of administration and their disbandment. They were trying to strip away and regulate both the organizational and personal pride that had come to rest in people’s hearts through too long a period of comfort or success within the Church. They were doing what Christ did, in a way, and flipping the moneychanger’s tables in the temple, driving out the goats and releasing the doves. This tendency in the Church often arises when the centralized administration forgets “first things” and becomes an organization run for its own sake and benefit. One could say that this is the basic instinct of the Reformation, as well, and we can see how it brings great advantages to evangelism, to quick dissemination and to the leveling of social convention that makes brotherhood difficult. It also carries with it the seeds of internal destruction, because, if it goes past a certain point, it creates something “other” than what once was, and replaces it with something completely discontinuous. This was how Buddha “reformed” Hinduism and ended up with a new faith, or how Smith “reformed” Christianity and ended up with Mormonism. It challenges, critiques, demolishes, and replaces. This is why it is also so dangerous.

If we observe history, these two basic orientations create cycles of formation and deconstruction within Church life. We can see these things playing out before our very eyes as the West strips away Christianity and becomes secular, all based upon Christian moral categories, while Russia, Africa and Southeast Asia all rapidly embrace conservative Christian values, based, paradoxically, upon a pagan love of power and the desire to fight the secular influence of the hedonistic West. One tries to eliminate all outward forms, while the other tries to amass them (like Russia building over 20,000 beautiful, traditional church buildings over the last 10 years). While we cannot maintain that there is one uniquely privileged ecclesial culture that has resisted the forces of entropy and acquiescence to human pride, the recognition of this cycle, the power to resist it through repentance and reconciliation, and the ability to constantly reaffirm the first principles of Christ's Gospel, is an eternally observable cycle of the created world's interaction with the Creator.

|

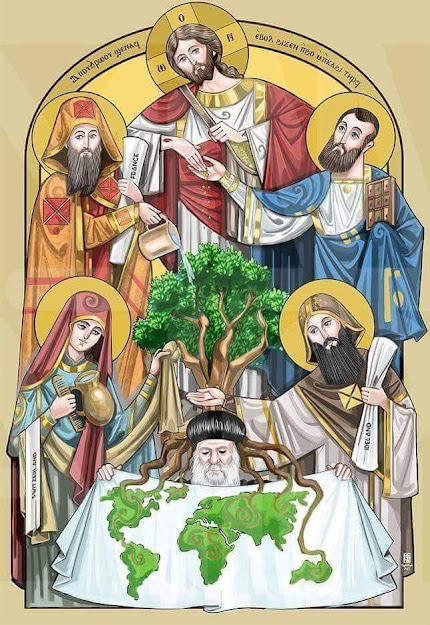

| A Coptic Depiction of the Growth of the Church as an Intertextual Process of Intergenerational Reception, Witness and Transmission Throughout Time and Space |

A Process of Reorientation

A Christian Tradition that remembers its mistakes, its imbalances, its struggles with drift in meaning and loss of proper orientation, is a Church that ensconces repentance and learning at its core, and realizes that salvation is a continuous process of repentance and growth, not only for the individual, but also for the corporate body. This process should be constant, and it is within this constant repentance and return that we express the unchanging foundation of our Faith, and express the Infallible Mind of the Church (while constantly expressing our own fallible natures). This process should always be founded upon and reinforce the revealed, creedal, immovable foundations of the Faith, and not used to deconstruct or question that which has been believed by all, in every place, and every time. It brings us into conformity with this “mean” and cannot be used (as many Anglicans and liberal Roman Catholics now understand it to mean) to critique or change this stable deposit of faith. This movement of “Ressourcement” is at the heart of the liturgical re-awakening of Western Christendom and has led to a revival of spirituality in the Neo-Patristic Movement in Eastern Orthodoxy as well. There is a tendency, unfortunately, to use the “gaps” that open up in the process of research and re-evaluation by those with an agenda to pack in their own, flawed, sinful proclivities. We can discerned this trend in many of the more liberal Eastern Orthodox circles as well. There must be a set limit to how this process is allowed to proceed. The Oxford Fathers, Dom Gregory Dix, and the Rev. Pearcy Dreamer, along with Fr. Alexander Schmemann and Fr. John Meyendorff should be our models for how this can be done, avoiding the slavophile political abuses of Lossky, Florovsky and Florensky, and the modernizing tendencies beneath the Roman Catholic “Nouvelle théologie” (although there is much here to learn, from de Lubac, Teilhard de Chardin, von Balthasar and Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI). Ressourcement is good as long as it cannot touch those universally received structures, theologically and liturgically, and is seen as a process for correcting our lives, rather than us correcting history.

One of the reasons more discerning Christian brothers in the various Apostolic Churches often react in anger to this process is that they, rightly, perceive that some will attempt to use it wrongly and overthrow the stable core of doctrine and practice. We cannot say that they are wrong or are being “fundamentalists”. St. John Maximovitch very clearly outlines the dangers of ecumenism in his enthronement speech, as do many other recent Eastern Orthodox saints. They see clearly how this process of repentance and re-orientation can be hijacked and used as a smoke screen for accomplishing the destruction of the Church’s process of receiving the guidance and theological reinforcement of the Holy Spirit throughout time. This is why Ressourcement must always be a return to what has been ecumenically received in the conciliar process, the Ancient and Orthodox Faith, and not the addition or subtraction of information through a process of expediency. It must be to bring us back to the mean, not to question or remove the mean itself.

This process of reevaluation is often mistaken as the primary value of the “Ecumenical Movement,” but this is a wrong understanding of what ecumenism has become. The process of ressourcement is found in the hard process of submitting to the Apostolic Gospel, the witness of the Undivided Church, full orthodoxy or doctrine and catholicity of faith, found through forgiveness, mutual submission, and godly love. Modern ecumenism, however, tries to minimize differences, protect our pride, and smooth over problems by adherence to the lowest common denominator, sacrificing truth for a political compromise and outward solidarity. This is essentially a negative and destructive pattern that must be resisted as a heresy. The Carolinian Divines, the Non-Jurors and the Oxford Fathers had a vision ressourcement in a restored and catholic Church of England. These noble intentions were derailed by Anglicanism’s tolerance for compromise, rooted in our political history and in the unresolved theological contradictions of the Reformation. Ecumenism has been incredibly hurtful and damning to us and to other churches, focusing on outward unity at the expense of the inner cohesion of doctrine and theological practice. It is a theology of “it doesn’t really matter” and attempts to minimize, rather than harmonize, deny rather than full flesh-out, differing views and experiences within Christian communities. In human relationships we would call this trait “dysfunctional” - because it tries to repair past conflicts by avoiding every mention of them. It is fearful on one side, and disbelieving on the other - because it doesn’t believe that the initial conflicts were valuable or revealed anything of value about us or God, but rather, merely holds history in contempt and downplays its relevance today. While we want ressourcement in our Church, centered around the Vincentian Canon and the shared life in all Apostolic Churches, we must always be on guard against ecumenism as a source of unity. They often appear similar, but their inner motivations are completely different. The first type desires submission to Christ as the “way, truth and life” and seeks His glory above all, realizing that man must humble himself before God and others in the process; the second kind desires that we merely “get along for mutual benefit” and does not require submission or repentance - but the “preservation of human dignity.” One is about Christ. The other is about our selves.

Summary

Our view on Biblical authority is different from the Protestant “Sola Scriptura” from the beginning, because we use the Ancient Church’s understanding of the Fathers as the hermeneutical context through which meaning is found. This is also not quite “Prima Scriptura” because it starts in the Faith of the Church, as confessed in the Creeds, and then interprets Scripture through a Christological paradigm that is centered on the Four Gospels, then through the New Testament, the Old Testament (with the Apocrypha), the Apostolic Fathers, the Ante-Nicene Fathers, the Ecumenical Councils the various local traditions of the catholic churches. We should not use the Reforming principle of Scripture Alone, or the idea that Scripture somehow interprets itself, because we do not see this in the Early Church or as a possibility with the miniotic epistemology that arises from postmodern deconstruction and Critical Theory (which shows how readers bring meaning to the text through inherited lexical categories that rest within the culture and not within the texts themselves). This makes sense with the process of the Scripture’s reception, canonization and transmission/preservation to us, where the work of the Church is constantly visible. The view that removes Scripture from this process is incredibly attractive, but historically untenable, and now, with alternative texts available, also a disprovable view. We see that the Scriptures never came to us in a separate, “pure” and “preserved” context that removes the agency of the Church or the constant interplay of cultural meaning. Scripture came to us in a process of transmission that did not hold the texts static or without local variants and dialectical/expressional differences. All of the textual streams - Hebrew, Septuagint, Peshitta, Byzantine, Alexandrian, Ethiopian, Latin and Slavic show this principle at work. If the Church interacted with Scripture, stabilizing its contents through doctrinal commitments, as we can see happening within all the various families of texts, then the Scriptures are not “above” the Church, but is at the “heart” of the Church, in a rich, symbiotic relationship. This vision is the only way that we can resolve the absolute catastrophic mental dissonance created by subjecting a love of Scripture and the “Sola Scriptura” view (that desires to hold Scripture above the Church instinctively) to the study of historical biblical texts, variants, families of Scriptures preserved by different local churches, and the advent of the provable methods of Textual Criticism. And, with this view of the preservation of Scripture within a divinely appointed and Spirit-filled culture of the Church, it makes sense of our ecclesiological choices - because, is within this continuous culture of Covenant Communities (righteous, patriarchal families that keep the priesthood and the sacrifices to God) that the Scriptures must continue to be preserved and propagated.

We seem to be saying the same thing over and over, but this is the historical point of the intertextual pattern that we have just described. We must repeat the same process of reception and promulgation in every generation. There is never a point when this cycle is finished, until the Lord returns. We have to take what was received, properly apply it with fear and trembling in our own lives, live out the works of repentance and faith, and teach this to our children (literally and spiritually), knowing that they will have to do the same thing all over again. At any time when we relax or stop returning to the deposit to re-appropriate God’s revealed truth, the process stops, and we have to start over in a long and painful process of re-evangelization, catechesis and sanctification. The point of the process is not academic knowledge, political power, or personal fame - the point is holiness of life, Christlikeness. To lose this is to lose any sense of purpose within the Christian life. This is what we are seeing in our “Post-Christian” context, in which evangelization in Western countries has become harder than mission work in traditionally non-Christian lands, because Christians have allowed the focus to be something other than the right worship of God and the reflection of His uncreated glory.

|

| A Modern Greek Icon of Christ Teaching the Apostles, a Paradigm of the Whole Church, an Icon of the Continued Process of Reception and Witness in Every Generation |

This is excellent. Thank you, Bishop. It is a well researched and thoughtful explanation of why the Protestant "sola scriptura" cannot be upheld factually, and why it has never been embraced by the Church. In my research in biblical anthropology (the science) it is evident that the Scriptures echo a much older Messianic Tradition which aligns very well with the Nicene Creed, except for the part about the Church. That tradition is already evident in the writings of the Horite and Sethite Hebrew dating to 6400 years ago.

ReplyDelete