Anglo-Orthodoxy in Contrast

|

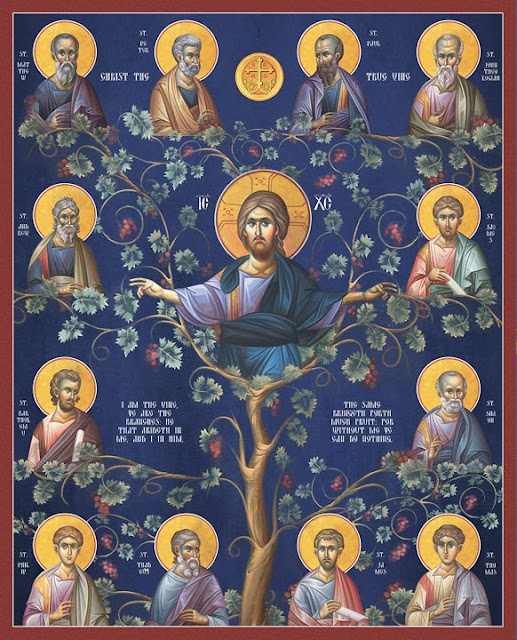

| Christ the True Vine, the Origin of All Apostolic and Orthodox Churches |

By Bp. Joseph (Ancient Church of the West)

An Anglo-Orthodox Perspective

As Anglo-Orthodox, our view of history is unique and highly beneficial to dialogue amongst local, catholic churches. Our view is that we are bound to receive and propagate what all the Nicene Churches received and ratified in the Seven Councils, because their ecumenicity stems from their universal reception, not from their declaration or promulgation from centers of ecclesial authority. In this we are very close to Eastern Orthodox, but not identical. We hold to an earlier ecclesiology, outlined in the Canons of the Apostles, which focuses on local administration and pastoral episcopacy, with the election of archbishops as necessary representatives to the state, but not as princely rulers. It maintains the equality of all bishops and the rule of the church through consensus at synod, and not of later Byzantine and Roman tendencies towards centralization and a hierarchy of bishops.

While our doctrinal views are firmly based upon the Seven Ecumenical Councils and the Undivided Witness of the Catholic Church in both East and West, this simplicity of understanding and interpretation are no longer received by the majority of the Canonical Eastern Orthodox Churches, which insist on a variety of "ecumenically binding" councils that occurred after the East-West Schism. These councils are the Council of Trullo (692, rejected by Pope Sergius I and the whole Western Church before the Schism and retroactively factored into the canon law of the Eastern churches), the Palamite Councils (1360-1380, after the Schism), the Panorthodox Council of Constantinople (1583), the Russian Council (1666), the Panorthodox Council of Jerusalem (1672), the Council of Constantinople (1872), the Panorthodox Synod (1878), and the Russian Council (1918). We would not accept these or their rulings without the reconciliation of Churches and a convening of truly Ecumenical Council, representative of all Local, Catholic Churches.

The contemporary situation within Eastern Orthodoxy shows that there is no consensus upon the number of Ecumenical Councils, from 7 to 9 to 13, and that there is a difference between the official proclamations of ecclesial centers (Constantinople and Moscow) and what has been finally received by all the local churches. This does not inhibit these centers from pushing their understanding as universal and binding, and has resulted in increasingly papal churches that see the locus of doctrinal authority within their own patriarchates and holy synods. Now that the Slavic and Greek canonical narratives have bifurcated with the 2018 Russian and Greek Schism, and there are two, conflicting definitions of ecumenicity that are at war within the Orthosphere.

We would differ from Eastern Orthodox Churches is in our belief that the Holy Spirit did not leave the Western Church after the Schism and that there is still Apostolicity and Fidelity to the Gospel within Churches that believe the Nicene Creed and maintain the laying on of hands for ordination, in succession to the Apostles. In this, we disagree with the Eastern Orthodox dismissal of Western Christianity and the belief that Western Orders and Sacraments are null and void. We also disagree with Papal claims that believe the Pope to be the Vicar of Christ and submission to him to be communion with Christ and His Church. This ability to agree with the other churches and also reject their innovations of doctrine is the defining characteristic of our Anglo-Orthodoxy.

This balance is surprisingly difficult to maintain, however, because it puts us at the center of cross-denominational dialogue, and also makes us everyone’s whipping boy! This historical view really does try to be “fair” and assume that everyone has noble motives, and also tries to be realistic and historically faithful, not picking sides. This is one of the reasons that the Anglocatholic Movement has created such amazing scholarship, but it also created an effete, ritualistic and self-absorbed attitude that has led to its downfall and use by secularists and liberals. It is also the reason why it tends to bifurcate - into groups that hole up and fear the continued attack of the world and other Christians, or into fantastically well-trained thinkers who are useless for evangelism and are completely out of touch with the pastoral needs of people. This is what we are trying to rectify in our diocese, the Anglican Vicariate of the Orthodox Archdiocese of America, by pushing away from the “Anglocatholic” identity and fully embracing our “rough and ready” Orthodox perspective. This vision is firmly rooted within the intentions of our founding bishops to create an "Orthodox Church for Anglicans" and plays out in our intercommunion with the Western Rite Orthodox missions that flow from the episcopal ministries of St. Tikhon of Moscow, St. Raphael Hawaweeny, St. John Maximovitch, St. Jean-Nectaire of St. Denis, and the Alexandrian Patriarch, Nicholas VI of thrice-blessed memory.

|

| St John's Vision of the Seven Candlesticks by Albrecht Dürer |

An Orientation in Orthodoxies

How would Anglo-Orthodoxy define the difference between the Coptic, the Greek, and the Assyrian Orthodox Churches? The simple answer would be doctrinal, seeing the primary differences as rooted in which of the Seven Councils they disagreed with and split off from. But, while this is an easy way to think of it, it is not historically true. The languages and cultures of the early, local churches were different, and the populations Christianized from very different places. There were already huge fault-lines between Pharisaical Jews in Mesopotamia and Hellenistic Jews in Alexandria.

The Mesopotamian Christians mostly converted from very serious, textually-based, legally-oriented Pharisees. You can see this orientation in the writings of St. Aphrahat of Persia. They used a typological hermeneutic and were extremely focused on Christ as Messiah and fulfillment of the Jewish Covenant. The Hellenistic Jews of Alexandria received the Gospel through the lens of Philo, the Jewish historian who wrote in a way to justify Judaism to the Greek Mind. He was the first to use “Logos” to mean God’s creative principle and another “personality” other than the Father, and this was echoed in the Gospel of John. Alexandrian Judaism had already started to describe God in a kind of “Trinity” before Christianity did - With the Father, the Logos and the Sophia showing the primary attributes of God, in a more philosophically defined way.

When Greek-speaking Alexandrian Jews converted, they also brought with them a temple practice that did not depend so much on Jerusalem. They had “another temple” on the Island of Elephantine, where their sacraments were, apparently, a meal (referenced in the Book of Ecclesiasticus, of Jesus Ben Sirach) that “partook in the sacrifices of Jerusalem.” This meant that most Jews in Egypt did not think they needed to go to Israel to be “real Jews” and that they believed in a kind of sacramental efficacy that could be shared through prayers and different temples, all joined together through God’s power.

The Development of Liturgies

The Jewish communities in Antioch, Edesa, Alexandria, Kerala, etc., had very different liturgical practices already in their Judaism, And this bled over into Christian worship. The Assyrian liturgy still has many of prayers that Babylonian Jews used, but Alexandrian Jews did not. Their use of the Barakoth prayer and the Qodesh in worship is like many Iranian Jews today. The Alexandrian liturgy is far more Greek in content and structure, focused on conveying cosmology and a vision of heaven, which is not found in the Litrugy of Mari and Addai. This influenced the Liturgy of St. James, which seems to harmonize the earthy, Judaic elements of Syriac Christianity and the lofty, Greco-Judaic cosmological focus of early Alexandrian liturgy. This is why scholars maintain that the St. James seems to be a combination of the Liturgy of St. Mark and the Liturgy of Mari and Addai. Most scholars think that the St. James took final form in the 3rd century, and was then immediately used by St. Basil as the basis of his new Greek liturgy, which was, in turn, modified by St. John Chrysostom.

The West used the Liturgy of St. James and St. John Chrysostom, along with the outline of a much simpler, much less fancy, ancient Roman Liturgy, and created the Proto-Gregorian Liturgy of St. Ambrose. This liturgy has a simple structure and very flowery, Eastern prayers. This is where the “Kyrie” comes from, as an import of the Greek prayers from the early St. John Chrysostom Liturgy into the Ambrosian context. The Early Church did not even change the language, but left it in Greek. The ancient Roman strata is actually very old, but most scholars believe the liturgy closest to what early Jewish Christians used is actually the Assyrian liturgy of Mari and Addai, closely followed by the Coptic liturgy of St. Mark/St. James. These are the oldest liturgies we have that come down to us intact, although there are quotes from others that are mentioned in the Fathers. Liturgy is extremely interesting area to study because one can trace the development and use of prayers from one area to another and can identify the earliest strata.

The Architecture of Different Receptions

This diversity of receptions is also reflected in the liturgical practices of the various local churches. As the common canonical principle expresses in Latin: “lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi” - “The law of prayer becomes the law of belief, which is the law of life.” The underlying assumptions of the various peoples interacting with the Gospel can be seen clearly in the development of the Christian Architecture. Alexandrian Christians were the first to build Christian Temples, while Christians in Syria and Mesopotamia were building worship spaces modeled on Synagogues, following their Jewish prototypes. Romans did not build temples or synagogues, but continued to meet in classical homes for a very long time, up until the end of the 3rd century. Their worship was shaped by the use of the Roman courtyard and a central baptismal pool, with a table set up in the “living room” under the eastern eves, for the sharing of a common meal. This is a Church of the East Church in Saudi Arabia, from the late 3rd or early 4th century. This structure typifies the Alexandrian temple model, and can even be seen in English church buildings in the Anglican Tradition, and is the basic blueprint for all Ancient Church buildings. There are always three doors at the front, a vestry on the right, a sacristy on the left, and the sanctuary in the middle, where the altar table stands. The Sacristy was used as a Baptistry, and it is still used like this in the Assyrian, Syriac, Coptic and Armenian Churches. The “Holy Door” in the middle would have had a curtain that pulled back to reveal the Mystery of the Eucharist, and the niche in the wall, under the Cross at the back would have been used to store the holy vessels and any reserve that was needed. Our English churches later replaced these doors with a rood screen, but still normally had three openings, just like this ancient Assyrian church building. In Byzantium these altar doors were decorated and became an Inconostasis. In Rome, after the Ciborium “tent” became popular over the altar in the sanctuary, the doors were replaced by a chancel barrier and eventually turned into the lifted, Tridentine altars, that consisted of up to nine steps, lifting the altar quite high off the ground and symbolizing the exalted, hierarchical nature of later Latin liturgy. It shows how the East still keeps traces of all of these early developments while they were obscured by later developments in the West.

Alexandrian Orthodoxy

Alexandrian Christianity gave early Christians the idea that the Church worship replaced the Jewish Temple worship, and that temples should be built in the tripartite form, with a narthex (outer court), a nave (court of the faithful), and a sanctuary (the “holy of holies”). This idea spread quickly throughout Christendom and is the reason why we have so much cohesion in styles of worship and architecture between ancient East and West. Syriac Christianity had a huge shift towards Alexandrian Christianity in the 5th century, as communication became facilitated by the Byzantine Roman Empire. Mesopotamian Christianity moved away from the Synagogue model, and Roman Christians started to build huge church buildings, based on the Roman Basilica at first, and later, after Justinian, based on the Alexandrian model. While worship and architecture became standardized, a few, underlying linguistic issues started to play a larger role in the definition of “Orthodoxy”, centered around a few, extremely influential Fathers.

In the Alexandrian Tradition, Origen became the most influential Christian thinker. He was brilliant and set the stage for much of what was to come. Origen noticed a lot of issues that no one else had been detailed enough to notice up until his studies. He noticed that there were huge difference in manuscripts of Scripture, in both the Greek versions of the Septuagint and in the Hebrew. He also saw how many of these differences had to have originated in textual variants a couple hundred years before Christ. He documented how the “Logos View” of Alexandrian Judaism was found in the New Testament, and how the Apostles had used quotations from the Septuagint in their Greek. The Alexandrian view, he rightly concluded, was not foreign or imposed upon Christian Scripture, but woven into it, just as the Judaic/Syriac/literalist view was also woven into the structure. Based on these observations, Origen proposed a layering of meaning in the text, that followed the general principles of his semi-Platonic cosmology. Origen was found wanting by many, including his own disciples. The Cappadocians (influenced by their grandmother, a disciple of St. Gregory Thermaturgist, who was a disciple of Origen) undertook the process of making his ideas less speculative and cosmological and more biblical. His proposal that Scripture be understood in three layers, the literal, the typological and the allegorical, however, stuck. This was used by St. John Chrysostom and the great, balanced saints of the Church to mine the depths of Scriptural meaning and application.

The Copts, West Syriacs and Armenians followed the Alexandrian School, and championed the Origenist method, the writings of Cyril of Alexandria and subsequent apologists for this school. The Alexandrian-oriented Churches of the Copts, Armenians, and later, the West Syriacs (Greek-speaking and informed ethnic Syriacs of the Holy Land) decided to draw the same kinds of lines in the sand over St. Cyril’s Christological terminology. They parted with the West over the difference in Greek over the Christological formula “in two natures” and proposed it should be “out of two natures,” implying that Christ’s nature was whole and not divided or at odds within itself.

Antiochian Orthodoxy

In Antioch, Diodore of Tarsus rose to preeminence as a teacher of Scripture, and his students, Theodore Mopsuestia and St. John Chrysostom turned the world of biblical exegesis on its head. The Antiochian School used Syriac to read the ancient Hebrew Scriptures and translated the Greek Old Testament into the Peshitta, and was focused on literal, historical context for understanding its meaning. The Alexandrian School, informed by Hellenic Judaism and Philo’s approach to the Old Testament, along with the theological systems developed by Ammonius Saccas, Origen, and later, by Athanasius and Cyril, were focused on studying Scripture from an anagogical (allegorical) perspective. Between these two schools, a large fissure grew, which was hard to bridge, and the theological differences started to entrench themselves within systems that did not recognize the other as “Orthodox”. Christianity split in three ways regarding the fault line between the Antiochian and Alexandrian Schools.

The Assyrians held only to the Antiochian School, which became the “School of Edesa and Nisibis,” as the Antiochian Fathers were persecuted and fled to Persia for supposed “Nestorianism.” The Church of the East/Church of Persia split with the West based upon their inability to say “Mother of God” in Syriac (“God” being “Alaha” or “Elohim”, the OT world used for the Father). Because they did not have a generic, pagan term for “Gods”, they could not say St. Mary was the “Mother of Divinity,” because that would make her the Mother of the Godhead, or the Mother of the Father, which is obviously heresy. They also were unwilling to assume Greek was a superior language, and unwilling to adopt a foreign term “Theotokos” as a doctrinal necessity. Thus, they dug in and this created an irreconcilable rift, rather than just give in as later, non-Greek-speaking churches would do. This gave place to some who were actually Nestorian heretics to shelter in the Church of the East, who taught that there were two “persons” in Christ, but these heretics did not shape the beliefs of the Aramaic-speaking Church. The official promulgation of the “Teshbokhta” of Mar Babai the Great, and later clarifications by Eshoyab II, clearly states a Chalcedonian theology of Christ’s hypostatic unity in two natures, fully God and fully man, and proves that the Church of the East was not truly “Nestorian.” However, after the break in communication between the churches, the West decided that the Church of Persia was heretical and had no authority, and thus, rejected any further contact with it (accept for a very short time of reprieve under Heraclius and Sergius of Constantinople during the Monothelite Heresy).

|

| The Traditional Architecture of an East Syriac Church, Showing the "Bema", the Raised Platform inherited from Jewish Worship where the Scripture is Read to the Congregation of the Faithful |

Byzantine Orthodoxy

The Greco-Roman Churches, focused on utility and balance as they were, synthesized the best of Antioch and Alexandria, through the writings of saints like St. John Chrysostom, St. John of Damascus and St. Maximos Confessor, into a Byzantine approach that was similar to, but not identical to St. Augustine, St. Ambrose and St. Gregory’s synthesis. Two “Roman” approaches emerged from the need to explain and balance the information and approaches that came out of the Eastern Fathers. The Byzantine Fathers tried to balance these issues philosophically, inventing layered schema, like Origen, to explain problems and contradictions. This is what St. Maximos did in his “Ambigua”, which was an explicit attempt to balance and explain issues of contradiction and variation within the different traditions of the Church. The Western Roman Fathers did something different. They relied upon a combination of legal thinking and the assumption of authority (which allowed them to dismiss the East when it didn’t match what they understood within their own Tradition). Legal thinking, reinforced by St. Jerome’s inaccurate translation of the Bible into Roman legal-compatible terminology, is what we now call “Augustinianism,” but it is really just the tendency to reduce ideas to their functional components and jettison nuance or contradiction. This has been the tendency of Western thought since before Christianity, and why Rome was both highly efficient and brutal. Appeals to authority, which was the other way that the Western Roman world dismissed Eastern thought with which they disagreed, originally focused on their church being the “church of the capitol” and then shifted to “original church established by Peter”, and then became enfleshed in the person of the Pope, who was first “St. Peter’s Representative,” and over time became “The Vicar of Christ.”

The Eastern and Western Romans then maintained an on-again off-again relationship until the “final” break in 1054 (although this is not really true, since there was documented cooperation for hundreds of years after this, and only really became “dug in” after the West sacked Constantinople in 1204). The difference in church focus and ethos between the two was really a difference in language, Greek and Latin, and the difference in their stereotypical interests - philosophy and law. After the West consolidated church and state under St. Gregory the Great (the Dialogist), the church polity of Rome looked very different from the church polity of Byzantium. It also ran differently, since the Roman State became a vessel for the Church, while, in the East, the Church became a vessel for the good order and function of the State. In Rome, the Pope switched out Emperors. In Byzantium, the Emperor switched out Patriarchs. One can see why Rome was constantly scandalized at Byzantium, thinking them impious and “Caesaropapist”, and longing to establish the pure and practically effective rule of the Pope over their unruly Eastern counterparts. The problem was, once they actually did it through force in the Crusades, the bitterness caused and the cultural damage was so great that the Eastern Roman Christians often invited Muslim rule. It didn’t work out well for them, and they were subjected to slavery and deprivation that completely destroyed their academic and philosophical institutions, all while the West grew stronger and more powerful. Under Islam, the Byzantines were not allowed to have libraries or even Bibles for almost 400 years. It was during this time that the Slavic Church grew up and became the “Third Rome”, with a hatred for the Romans (who had abused the East), and a lack of respect for the Greeks (who were slaves to the Turks). Thus, the stage was set for yet another cultural manifestation of Christianity with unique perspectives, cultural priorities, and interpretations of history.

|

| The Byzantine Altar shows the Development of the Bema, the Holy of Holies, and an extremely hierarchical Cathedra, or “Episcopal Throne,” based off of the ancient Roman Senate |

Summary

Ultimately, we ended with separate local, catholic churches at the ends of each of these cultural responses to the different approaches. The Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox, the Byzantine Orthodox and the Roman Catholics all resulted from struggling with issues of Scriptural interpretation through Tradition, informed by the underlying cultures and languages of the people in their different places. The cohesion between them is all astonishing, especially when one considers how different their cultures really were, and goes a long way in supporting the idea that the Apostolic Deposit is both real and transforming. The difference upon which they split also seem extremely small, considering how absolutely diverse and philosophically amorphous contemporary Christianity is today.

|

| Traditional Greek Icon of St. John the Apostle's Vision of the Churches of Christ in the Vision of the Apocalypse, Revelation 1:13 |

Thank you for writing this, your Grace. It was really helpful. I long (without much real hope) for the day when my bishop will recognize your valid apostolic succession.

ReplyDeleteInformative and enlightening. May the Lord bring together in practical terms, his Church which only divided over their different traditions. Being the "whipping boy" Anglo-Orthodox/Catholics both have a strength and weakness in being able to step back and look at these things more objectively than many of our borers and sisters.

ReplyDelete