On the Use and Meaning of Religious Art

|

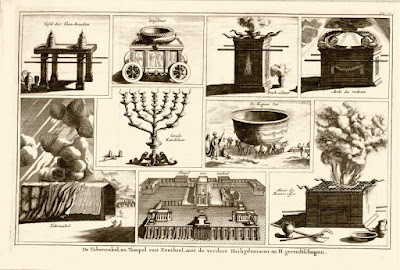

| The Implements of the Hebrew Temple |

|

| The Implements of the Christian Temple |

By Bp. Joseph Boyd (Ancient Church of the West)

One of the greatest differences between Apostolic Christianity and Protestantism is the very different focus on "externals," the set use of symbols, art, panorama, drama and ritual to convey the Gospel. While I would concur that many of these things "do not save" or are not "fundamentals of the faith," the Apostolic tradition sees these things as essential in communicating the catechetical process and passing on the form and substance of a saintly life. The physical world being incorporated into the spiritual process of salvation is not a bad thing, and does not need to be artificially stripped away, because God took on flesh and still remains a man. Like the physical body, the Body of Christ, His Church, is made up of many physical members, and will be physically resurrected at the End of Days. We do not strive for a disembodied, gnostic, heavenly existence, but a incarnate, resurrected, lively and bodily eternity with our Creator. All of creation will be redeemed and all the material world will reflect God's glory. Therefore, it is completely legitimate to "redeem matter" by using physical things, beauty and patterns/rituals to tell the story of God's Gospel. Within the life of the Church and the continuity of the physical forms from one generation to another, we find the "Mind of the Church," which is the point of agreement and mutual recognition that holds us in a communion of love and spiritual humility, imparting the Gospel through physical relationships.

The disconnect between the historical art of the Church and the contemporary use of art in Christian worship happens because most people do not understand the continuity of the Early Church with what was before, in 1st Century Jewish practice, and they do not accept the authority of the Early and Conciliar Church as being definitive as to how this continuity was interpreted and applied within the New Covenant Community. If they are aware of the continuity, many try to “return” to a standard that does not factor in Jewish developments after the Fall of Jerusalem in 70AD or the anti-Christian Council of Jamnia, where practices and texts were standardized by the Jewish Faith so as to negate a Christian reading of those aspects of Hebrew Tradition. While I understand their objections to an incarnated, ritualized “religion," mistaking honor attributed to physical things with the worship of the invisible God, I do not agree that this negative perspective is historically accurate or sincere to the core values of Christianity. It is just too much of a theme in the Early Christian Fathers to ignore. We see the struggle for continuity in St. Hippolytus’ liturgical catechism, in St. Irenaeus’ “On Apostolic Tradition,” in the "Didascalia Apostolrum," in St. Cyril of Jerusalem in “On the Divine Liturgy”, etc., where the Christian liturgy was already ancient by the end of the 3rd century and veritably unchanged from today. What I have come to conclude is that there was radical continuity between the Old Testament and how the Apostles and their followers built, practiced and maintained the Church - keeping the continuity of the priesthood, the evening and morning prayers, seasons of feast and fast, holy days, and a sacrificial understanding of covenant and our interaction with it.

The disconnect between the historical art of the Church and the contemporary use of art in Christian worship happens because most people do not understand the continuity of the Early Church with what was before, in 1st Century Jewish practice, and they do not accept the authority of the Early and Conciliar Church as being definitive as to how this continuity was interpreted and applied within the New Covenant Community. If they are aware of the continuity, many try to “return” to a standard that does not factor in Jewish developments after the Fall of Jerusalem in 70AD or the anti-Christian Council of Jamnia, where practices and texts were standardized by the Jewish Faith so as to negate a Christian reading of those aspects of Hebrew Tradition. While I understand their objections to an incarnated, ritualized “religion," mistaking honor attributed to physical things with the worship of the invisible God, I do not agree that this negative perspective is historically accurate or sincere to the core values of Christianity. It is just too much of a theme in the Early Christian Fathers to ignore. We see the struggle for continuity in St. Hippolytus’ liturgical catechism, in St. Irenaeus’ “On Apostolic Tradition,” in the "Didascalia Apostolrum," in St. Cyril of Jerusalem in “On the Divine Liturgy”, etc., where the Christian liturgy was already ancient by the end of the 3rd century and veritably unchanged from today. What I have come to conclude is that there was radical continuity between the Old Testament and how the Apostles and their followers built, practiced and maintained the Church - keeping the continuity of the priesthood, the evening and morning prayers, seasons of feast and fast, holy days, and a sacrificial understanding of covenant and our interaction with it.

Art must be accountable to its content and context in order for it to serve the purpose of the Church. Every generation’s methods are slightly different, as resources and techniques change. One generation uses egg white and mineral pigments, while another may use light and lenses, but both must be accountable to the message that they portray, and both must communicate the historical context of that message to the best of its ability. Thus, historical Christian art that is culturally close to the time of Christ is extremely valuable, and will never diminish in its importance to the Church, regardless of the aesthetic tastes of the contemporary culture. This is because of the “intertextuality” I keep writing about in my blogs. Texts don’t carry their own meaning. That meaning resides in the culture that produced the texts and the meaning is rediscovered in every generation by the interplay between the culture and the texts. When the original cultural context is lost, the culture receiving the text reinterprets it, and you end up with Protestantism or Mahayana Buddhism - a new teaching that claims continuity, not based on truthful inheritance, but based on misunderstanding and misappropriation. When we talk about art this is extremely important because culture is deposited in icon, song, ritual, food, architecture. Without these things, meaning gets lost. That’s why the Church is best understood as a culture, and a very specifically historically oriented and crystalized one. The Fullness of God’s Love and the Economy of Grace was only revealed once - and it was in a Greco-Roman-Hebrew-Aramaic cultural milieu, a cultural crossroad that fully lays bare our need for God and His love for us.

There is also bad Christian art that obscures and contemporizes, attempting to make the Gospel and its culture acceptable to us, rather than the other way around. This is the bad art of the Reformation, with wisemen in codpieces and the Blessed Virgin in Elizabethan collar; the Christian industrialist’s “God of Concrete, God of Steel” and the floundering aesthetic of Episcopalianism and the Post-Vatican II Catholicism of “make it attractive to non-Christians to get more people in the door.” That’s not how covenants work. The church is not for the un-churched, and the art of the church is to teach every generation our historically-based faith, our traditions, our understandings, not as a process of making things attractive, but a process of sincere catechesis, each generation faithfully passing down the message as it was passed to them, the Living Gospel, the Paradosis/Tradition of St. Paul, the fullness of the Holy Spirit in the Church.

These are all painful to people with modern artistic sensibilities, because they are anti-humanist, anti-expressionist, anti-egalitarian (ancient people have more right to an opinion than we do). Everything in the contemporary Western mentality teaches us that this is wrong; that history should be informed by our opinions, or, at least, it should be a dialogue. It is painful to our modern egos to find that we have nothing to offer. We do not like being told what to do and having to sit quietly and listen, like the children we are, to our elders. The same is true for art. We have a choice, though, like all children do. We can sit and listen, and let the words become our own and eventually write poetry, paint pictures and sing songs with our acquired fluency… or we can rebel, act out, and scribble on the walls in undisciplined and bratty rage.

Unfortunately, many seem to prefer the crayon drawings of today to the holy icons of the Early Church, thinking that they somehow are more “authentic”, “personal” and "attractive to the unchurched.” The problem with this is that it obscures, and as Scripture is reinterpreted to fit our culture, and our culture is deemed the aesthetic standard through which Church art must abide, intertextuality is completely lost. The salvific element of Christian art pointing to that which was, to that which is not us, to a culture that is, for all intents and purposes, permanently foreign, is lost. This leads many to conclude that their cultural sensibility is the standard and their thoughts are God’s thoughts and their ways are God’s ways. This kills repentance, awe and human smallness. Instead, it puffs man up with the first sin, pride, taking him off the narrow, difficult, tiring pathway to heaven that is only undertaken by those who accept that they are deficient and lacking of themselves, and putting us on an easy, enjoyable, adrenaline-pumping slippery slide to hell.

Comments

Post a Comment