On Pastoral Priesthood

By Bishop Joseph Boyd (Ancient Church of the West)

The Theological Meaning of the Pastoral Ministry

“But the aim of the (priestly, as opposed to medical) art is to provide the soul with wings to rescue it from the world, and to present it to God. It consists in preserving the image of God in man, if it exists; in strengthening it, if it is in danger; in restoring it, if it has been lost. Its end is to make Christ dwelling the heart through the Spirit, and, in short, to make a god sharing heavenly bliss out of him who belongs to the heavenly hosts.”[1]

The Church is, as a reflection and continuation of the ministry of its Lord, a divine-human institution, meshed as it is between the created and uncreated, exposing man to both the best and the worst of human experience. The whole purpose, then, of this economy is the reception of life, a “modus vivendi" that allows for the survival of the human race, the divine-human faith, and a continued experience of the presence and transformative energies of God - a renewed society that is the reflection of Light of the World, warmed by the presence of God’s life-giving and creating energies. Thus, human flourishing and abundance of life is the characteristic of the Church’s situation. Flourishing requires nurture, and this is what pastoral ministry is - the care of the divine economy of God’s grace, manifest in human society, for the protection, building up and blossoming of the created would in the faith, hope, love and light of the uncreated presence who is which us, God with us, the Incarnate Lord, Our Savior Jesus Christ!

At the center of the Church’s worldview is the profound realization of the implications of being created. “For the [Catholic], the idea of creation implies a duality of existence: God and creature, who is brought into that existence by a long freedom, pure and absolute, “ex mera libertate”. The unchanging still point which God is, does not mean that He is uninvolved in human lives; nothing could be more unorthodox that such a teaching. After all, He has “pitched His tent among us,” and thus is, at once, always with us, and always coming to us. The still point of this synthesis is God’s nature or essences (ousia), which is in no way man’s nature or essence. What man shares is God’s energy (energia), in which God has given Himself from the moment He breather life into the dust. But there is - and this is crucial for understanding the synthesis of human existence - a difference between God’s essence and energy. It is the energy which is ours to have - and it always comes “ad extra.” Creation has other implications vis-a-vis this synthesis. God calls all creation “out of nothing” (ex ouk onton) to be a new creation, which becomes the bear and carrier of His very image or idea (His icon), and yet without ever being existentially identified with it, the result being precisely a confusion in the order of that synthesis. A human cannot merely say of himself, “I am that I am” - that is, that one exists by some “right of nature.” In short, Eastern theology will say that we do not exist by some sort of intrinsic cause or nature of our own, but solely by the grace of the Causer.”[2]

The Church is the imprint of the Kingdom in the world, like the impressions of an invisible hand upon the sand. While the Kingdom is within the Church, not everything that calls itself Church is within the Kingdom. Its unity and duality is a mystery, reflected in Christ’s parable of the field, strewn with wheat and tares. The discernment needed for the pastor is to walk in this field, tending it until the harvest, without the apostolic compulsion that received Christ’s rebuke, attempting to “uproot the wheat with the tares”. The Church is not the Kingdom fully realized. The Church is processing into the Kingdom, and the Kingdom is manifesting in the Church, but one is still fallible, changeable, striving, struggling, continuously moving. The other is a heavenly reality, a fully-realized promise, the true state of a universe held up by a ontological connection to its Maker. The Kingdom is Christ’s reign, accomplished through His Work, now hidden, present within believers, and fully revealed at the Second Coming. The problems of canon and law that we will look at later in this paper come from a misperception that equates the Church with the Kingdom - and thus ventures to believe that the Church is already perfect, already static, already fully realized. Those who believe this cannot be pastoral, because the shepherd’s role is to guide the sheep as they move from pasture to pasture, from the fold to the water, and from the water to the green grass. Those who think of the pastor as a guardian in a fortress would have the sheep remain in one place and die without food or water.

The Church is transformed by the life of Christ in motion, in the obedient practice of that which was given by Christ - this liturgical manifestation of Christ’s commandments conform our bodies, our physical reality, to the patterns of Christ’s energy, expressed through the Holy Spirit. This is the goal of the Church as a “being-restored” Creation, the transformation of the world by God’s Life, expressed through obedience to His ordinances.

In “The Symbol of the Kingdom”, Fr. Alexander Schmemann shows how these sacraments function as “symbol”, not standing for absence, but bringing an eternal state of heavenly truth together with our temporal space, time and material substance. This view demonstrates how Christ unites eternal reality with our earthly practice in the Life of the Church, which enabling us to unite two realities, and both picture and participate in the Work that Christ has accomplished “Once and For All”.

His most moving and profound passage states, “…The Kingdom of God is the content of the Christian faith - the goal, the meaning and the content of Christian life. It is the knowledge of God, love for Him, unity with Him, and life in Him. The Kingdom of God is the unity with God as the source of all life, indeed as life itself. It is life eternal: 'And this is eternal life, that they know Thee the only true God…' (John 17:3). It is for this eternal life in the fulness of love, unity, and knowledge that man was created: 'In Him was life and the life was the light of man' (John 1:4). But man lost this in the fall, and by man’s sin, evil, suffering, and death came to reign in the world. The 'prince of this world' came to reign; the world rejected its God and King. but God did not reject the world. 'He did not cease to do all things until He had brought us up to heaven, and had endowed us with His Kingdom which is to come' (Anaphora of the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom).

“And now, ‘the time is fulfilled, and the Kingdom of God is at hand’ (Mk 1:15). The only begotten Son of God became the Son of Man in order to proclaim and to give to man forgiveness of sins, reconciliation with God, and new life. By his death on the cross and His resurrection from the dead He has come to reign. Christ reigns, and everyone who believes in Him and is born again of water and the Spirit belongs to His Kingdom and has Him within himself. 'Christ is the Lord.' This is the most ancient Christian confession of faith, and for three centuries the world, in the form of the Roman Empire, persecuted Christians who spoke these words for their refusal to recognize anyone on earth as Lord except the One Lord and One King.”

Fr. Alexander brings his thesis home with a final observation. “The Kingdom of Christ is accepted by faith and is hidden 'within us.' The King Himself came in the form of a servant and reigned only through the Cross. There are no external signs of this Kingdom on earth. It is the Kingdom of 'the world to come,' and thus only in the glory of His Second Coming will all people recognize the true King of the world. But for those who believed in and accepted it, the Kingdom is already here and now, more obvious than any of the ‘realities’ surrounding us. ‘The Lord has come, the Lord is coming, the Lord will come again…’ This triune meaning of the Aramaic exclamation 'Maranatha!' contains the whole of the Christian’s victorious faith, against which all persecutions have proven impotent.”[3]

After Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s evangelistic vision of the enfleshment of the Gospel in the Church, Fr. John Meyendorff undertakes the process, and shows how the element of time in the life of the Church centers on the time of Christ’s Passion, the time commemorated during Holy Week, typified in Holy Saturday and Christ’s victory over death. “The incarnation itself is a story, a continuum, a process. In becoming man, the Son of God does not assume an abstract humanity, but becomes a human individual, Jesus of Nazarath, who was born as a child, “grew in wisdom and statute,” and lived to maturity in human life. Eventually, He met with the hostility of various religious and political groups in the society in which He lived, was crucified and died on the cross, but rose from the dead on the third day. His death and resurrection - the facts that constitute the very foundation of the Christian faith - were events occurring in time.”[4]

The Question of Pastoring and Power

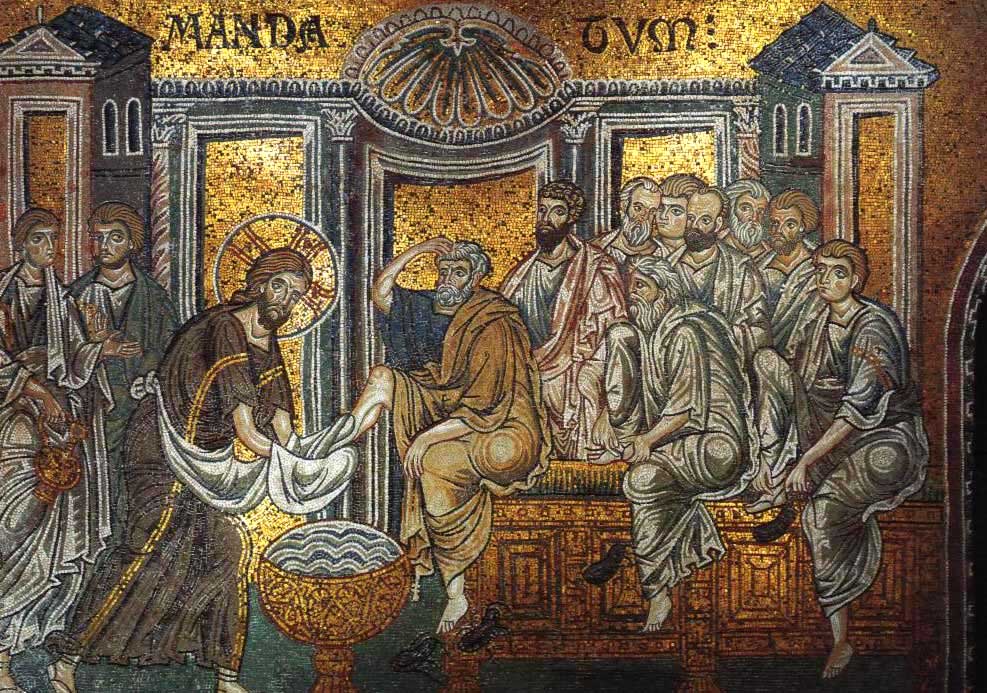

The morality of violence may seem like a topic outside the consideration of the pastoral ministry - a man of the cloth being a man of peace - but, this is not necessarily true, because violence is a form of coercion, and most pastors are daily faced with the edges of a moral paradox - “How far can I exert influence before it becomes coercive and begins to undermine the autonomy of the individual and the autonomous family unit?” Priests who do not ask themselves this question are almost always manipulative and turn the pastoral ministry of servanthood into the manipulative, self-exulting puppetry of the cult. This is especially easy in Orthodoxy, where the reverence for tradition and the multitude of mysterious and decontextualized forms lends an air of magic and mystery - leading aspiring cult leaders to “serve” the Church like a wizard or magician, instead of like Christ with His loins girt and a towel as His priestly stole.

In “The Morality of War”, Stanley Harakas offers a complex commentary on the questions that the Church did and did not answer about power. This goes to the heart of the question on the meaning of the Pauline "minister of God for good, not bearing the sword in vain" idea, a paradox at the center of the modalities of the Church's incarnation in society. There is a good argument for rejecting offensive violence from the Church’s Tradition, but allowing defensive actions for the protection of moral good. St. Nikodemos’ “Rudder" calls for complete abstinence from coercion and power on the part of those ordained to serve the Gospel, but allows for those Christians who serve in the military and the government to fulfill their role as "avengers of wrath upon those who practice evil", per St. Paul's admonition in Romans 13. This is a more complex, gradient approach to the realities of the Christian interface with the fallen world than either the "Just War" or the "Christian Pacifism" stance. A logical or consistent answer does not exists - both the Christian civilizationalists and the Christian monastic pacifists have bitter pills to swallow. Because the Church Catholic does not teach the “overly-simplified” Protestant view of “Sola Scriptura" as self-interpretive hermeneutic, we know the answers cannot be textually determined, but must be left as antimonies through which the Holy Spirit freely leads the Church.

There is, however, the question of what Christians are to do with power once they have it, the "Constantinian Question", and this leads us into the process of discerning what actions best reflect Christian truth. This is the thought process that must drive the pastor as “father”, the “economos” of the House of God in his place. The iconic analogy of “Church as Economy” was the primary source of theological inspiration in the 3rd century amongst the Cappadocian Fathers’ writing on the pastoral role. The priest was, at his best, a “Chief Spiritual Economic Officer”. In the process of embracing this vision, Plato’s Republic gave way to St. Augustine's Civitas Dei, and the Catholic Church began to picture the plan of salvation as an economic system in which the Church played a vital, managerial role.

As both Harakas and Boojamra both show, the Church did not eradicate coercion, slavery or violence and neither did the Holy Scriptures. While acknowledging the brotherhood of all men and the universal likeness of God, the canons of the Church never undermined the unequal social order or upended the Roman caste system. The argument against a Christian taking power or fighting wars, such as made by the Russian monastic “Non-Possessors”, neglects social and moral responsibility in predominantly Christian societies or in situations where the powerful or talented convert in a position of responsibility. These questions and contradictions go to the heart of the incarnational paradigm and are challenging because we can only maintain then antimony, "building a wall around the mystery", rather than solving the contradiction through the application of Aristotelian principles. The Eastern position, being revealed as it is by an illogical juxtaposition of opposites in a "God-Man", can never be asked to solve the problem. If one position takes precedents up and against the other, you end up with a completely "divine" and idealistic position of cultural "Monophysitism" or, if denying the ability of social order to channel God's grace in the midst of imperfections, a position like that of a cultural "Historical Jesus" - a human myth completely devoid of reality. In the end, there must be a personal response that allows for the position of the person in society to fulfill their moral obligations.[5]

The Solution to the Problem of Pastoring

Problems of pastoral theology must be addressed with an understanding of the dynamic tension that must be maintained between theology and practice, manifested in the motives of apologetics, teaching and practical application of truth to life and the world. Theology serves these pastoral goals, goals that God Himself and established and showed to be His primary concern through the incarnation of His Son, the Lord Jesus Christ. Practice must not be minimized to clinical categories, to therapy, or to personal experience, but encompass all factors of the Church’s Life - from the worship of the Liturgy to the private counsels of confession. It must encompass all of the theological applications to human life and is built upon discernment and perception of consciousness, the fundamental platform upon which all other sensibilities and thought processes run.[6] This is achieved through “Paradigm Coherence”, a “Truthful Presence” and “Theological Nerve”, which is “the courage to turn human situations into a theological task”.[7] Above all, the pastoral ministry requires integrity, which can only be found in a truthful estimation of one’s own struggles and sinful tendencies. This brutal honesty is a rarity, is difficult to find and maintain, and is the opposite of the “pastoral pathology” of those who wish to be respected through “supernatural means”, undercutting all reasons for pastoral ministry outside of those which Christ’s Incarnation demonstrates - Love, humility and a commitment to serve, “though the more I love you, the less I be loved.” (2 Corinthians 12:15)

Footnotes:

[1] St. Gregory of Nazianzus, in Philip Schaff’s “Niceane and Post-Nicene Fathers”, Series 2, Vol. VII, Translated by H. A. Wace, pg 209

[2] Fr. Dr. Joseph Allen, “Orthodox Synthesis”, SVS Press, 1981, pgs 13-14

[3] Fr. Dr. Alexander Schmemann in “Orthodox Synthesis”, Fr. Dr. Joseph Allen, Ed., SVS Press, 1981, pgs 39-41

[4] Fr. Dr. John Meyendorff in Ibid, pg 51

[5] Fr. Dr. Joseph Allen, Ed., “Orthodox Synthesis”, SVS Press, 1981, pgs 80-81, 189-209

[6] Fr. Dr. Joseph Allen, Ed., “Orthodox Synthesis”, SVS Press, 1981, pg 100

[7] Ibid, pg 101

Comments

Post a Comment